Key Takeaways (expand)

- A diet abundant in a variety of vegetables and fruits reduces risk of nearly every chronic and infectious disease

- An ideal goal for vegetable consumption would be to eat 500 to 600 grams per day (about 5 to 8 servings) and as much as you want above that

- An idea goal for fruit consumption would be to eat about 300 grams per day (about 2 to 3 servings)

- Frozen and canned options are just fine! And, it’s okay to work up to these goals slowly over time. Progress > Perfection!

The foundation of a Nutrivore diet is whole and minimally-processed foods, including a wide variety of vegetables and fruits.

An ideal goal would be to eat 5 or more servings of vegetables daily, plus about 2 or 3 servings of fruit daily. We’re going to dig into the science behind this recommendation, but right out of the gate, I want to emphasize that it’s okay to work up to this lofty goal—every step in the right direction counts! And even though scientific studies show the more vegetables we eat, the better, there’s a substantially bigger impact on health going from zero veggies to any than there is going from quite a lot to even more.

It’s also best to eat a wide variety of veggies and fruit, including representation from all of the major vegetable and fruit families, and all of the different color families. Let’s dig into how we can benefit from a diet abounding in vegetables and fruit!

All the Benefits of Eating Fruits and Vegetables

An estimated 7.8 million deaths from all causes could be avoided globally each year if everyone consumed 800 grams of veggies and fruits every day.

Studies consistently show that eating a diet rich in vegetables and fruit is the most important dietary factor for improving health. Eating vegetables and fruit in abundance lowers risk of:

- cancer

- cardiovascular disease

- type 2 diabetes

- obesity

- chronic kidney disease

- osteoporosis

- bone fragility fractures (including hip fracture)

- cognitive impairment

- dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease)

- neurodegenerative diseases

- asthma

- allergies

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- age-related macular degeneration

- cataracts

- glaucoma

- depression,

- ulcerative colitis

- Crohn’s disease

- rheumatoid arthritis

- inflammatory polyarthritis

- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- acne

- seborrheic dermatitis

Wow! A 2019 review additionally summarizes emerging evidence for a role for vegetable and fruit intake in lowering markers of inflammation and reducing risk of infection, migraine headaches, colonic diverticulosis, diverticular disease, acute diverticulitis, eczema, and more!

Every serving of fresh, whole vegetables or fruit we eat daily reduces the risk of all-cause mortality (a measurement of overall health and longevity) by 5% to 8%, with the greatest risk reduction seen when we consume eight or more servings per day. In fact, consuming 800 grams (equivalent to 1.75 pounds, or 28 ounces) of vegetables and fruits daily reduces all-cause mortality by a whopping 31% compared to eating less than 40 grams daily.

In fact, a 2017 meta-analysis showed that 2.24 million deaths from cardiovascular disease, 660,000 deaths from cancer, and 7.8 million deaths from all causes could be avoided globally each year if everyone consumed 800 grams of veggies and fruits every day! Wow, again!

Nutrivore Is a Game-Changer—This FREE Guide Shows You Why

Sign up for the free Nutrivore Newsletter, your weekly, science-backed guide to improving health through nutrient-rich foods — without dieting harder —and get the Beginner’s Guide to Nutrivore delivered straight to your inbox!

Why Variety Is Important

In addition to eating enough vegetables and fruits, choosing a wide variety is extremely important. Each family of vegetables and fruits is independently beneficial thanks to containing varying phytonutrients and fiber types. This means that eating a serving of 5 different vegetables and fruits per day delivers more benefits than eating 5 servings all of the same vegetable or fruit.

Studies have also shown that the various vegetable and fruit families offer different levels of protection against different chronic diseases. For example, cruciferous vegetables, green and yellow vegetables reduce the risk of cancer more than other vegetables or fruit; but, non-cruciferous veggies, raw veggies and citrus fruit reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease the most. Again, we get the best coverage against a wide range of chronic diseases by choosing a variety of vegetables and fruits from different families.

An important 2018 study also showed that people who eat 30 or more different plant foods each week have a substantially healthier and more diverse gut microbiome than people who eat 10 or fewer plant foods per week, which is extremely important for supporting our overall health. Other studies have confirmed that eating a wider variety of fruits and vegetables improves health. For example, a 2018 study showed that there was an inverse linear relationship between vegetable variety and coronary heart disease, meaning that the more different types of veggies you eat, the lower your risk.

The easiest way to apply this insight from scientific studies it to think of each vegetable and fruit family (cruciferous vegetables, leafy greens, parsley family, onion family, root vegetables, squashes, mushrooms, citrus, apple family, berries, melons, tropical and subtropical fruits, etc.) as its own food group, aiming to choose from as many different vegetable and fruit families as possible every day.

In addition, the pigments that give different fruits and vegetables their characteristic colors are phytonutrients; and, each one of these classes of phytonutrients have distinctive benefits, which is why “eating the rainbow” is important for ensuring that we consume a wide variety of these beneficial compounds. A 2022 umbrella review that included 86 studies, 449 health outcomes, and data from over 37 million participants concluded that 42% of health outcomes were improved by color-associated pigments, and that those health outcomes that were improved by multiple pigments included body weight, lipid profile, inflammation, cardiovascular disease, mortality, type 2 diabetes and cancer. In fact, this review shows that color-associated fruit and vegetable variety may confer additional benefits to population health beyond total fruit and vegetable intake. So, aim for dietary representation of each of the five color families for fruits and veggies: red, orange and yellow, green, blue and purple, and white and brown.

Studies have also shown that people who choose more different kinds of fruits and vegetables also tend to eat more of them, attributable (at least in part) to developing more of a liking for fruits and vegetables when consuming a greater diversity of them, so fighting veggie boredom just might be the key to eating more. Most grocery stores contain 50 to 80 different vegetables, mushrooms and fruits, so this isn’t as intimidating as it sounds!

Everything You Need to Jump into Nutrivore TODAY!

Nutrivore Quickstart Guide

The Nutrivore Quickstart Guide e-book explains why and how to eat a Nutrivore diet, introduces the Nutrivore Score, gives a comprehensive tour of the full range of essential and important nutrients!

Plus, you’ll find the Top 100 Nutrivore Score Foods, analysis of food groups, practical tips to increase the nutrient density of your diet, and look-up tables for the Nutrivore Score of over 700 foods.

Buy now for instant digital access.

How Much Fruit versus Vegetables?

It’s also worth emphasizing that eating both vegetables and fruits is more protective than eating one or the other, so it’s best not to go whole hog on veggies at the expense of fruits, or the other way around. In fact, fruit’s reputation as “nature’s candy” in health and wellness communities is not supported by scientific evidence—our health benefits much more from consuming a moderate amount of fruit compared to abstaining.

While the results revealed no upper limit to the benefits of vegetable intake, the sweet spot for fruit intake was 300 grams daily.

A 2017 systemic review and meta-analysis looked at how all-cause mortality was impacted by varying intakes of 12 different food groups: whole grains and cereals, refined grains and cereals, vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, eggs, dairy products, fish, red meat, processed meat, and sugar-sweetened beverages. This analysis revealed non-linear relationships between how much of a particular food group we eat and how it impacts our health. While the results revealed no upper limit to the benefits of vegetable intake, the sweet spot for fruit intake was 300 grams daily (about 2 or 3 servings, depending on the fruit). Intakes of fruit over 400 grams per day were not as beneficial as 300 grams, but the good news is that even intakes of 600 grams of fruits per day was superior to no fruit at all!

A good rule of thumb is to aim for at least 5 servings of vegetables, and about 2 to 3 servings of fruit per day.

Want to know the top 25 foods for this awesome nutrient?

The Top 25 Foods for Every Nutrient

The Top 25 Foods for Every Nutrient e-book is a well-organized, easy-to-use, grocery store-friendly guide to help you choose foods that fit your needs of 43 important nutrients while creating a balanced nutrient-dense diet.

Get two “Top 25” food lists for each nutrient, plus you’ll find RDA charts for everyone, informative visuals, fun facts, serving sizes and the 58 foods that are Nutrient Super Stars!

Buy now for instant digital access.

What Is a Serving?

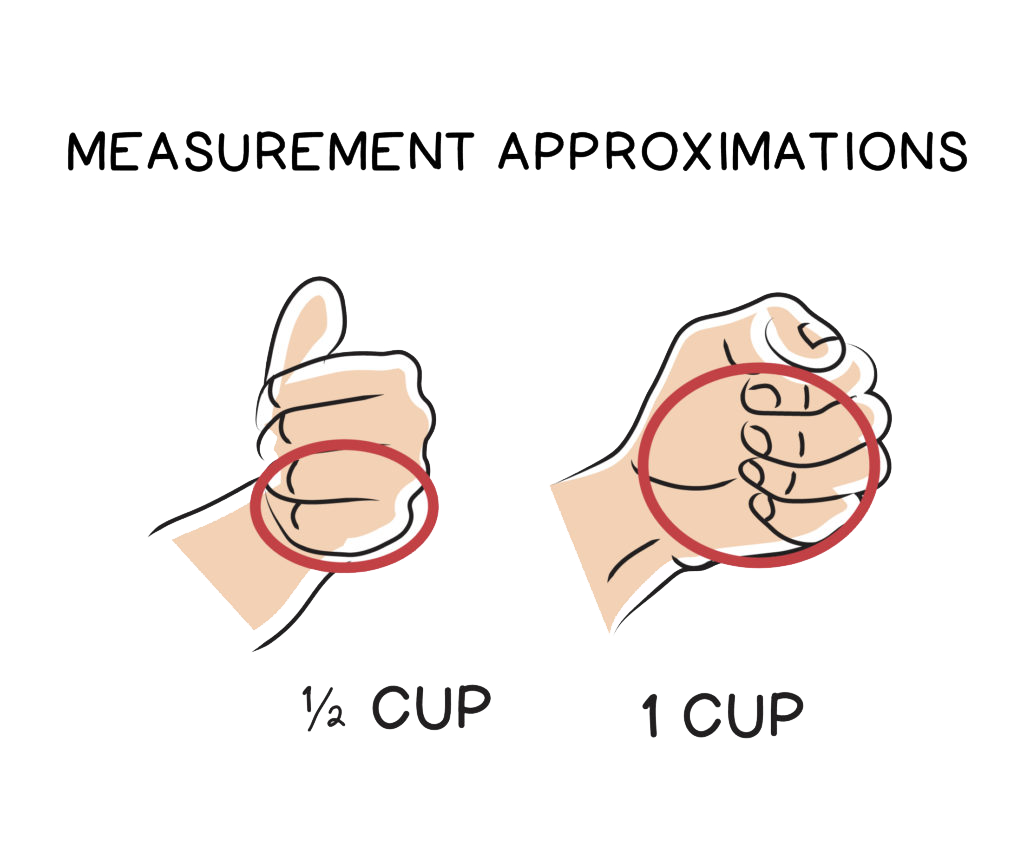

A serving is standardized to 1 cup chopped for raw vegetables and fruits (typically translates to 1/2 cup to 2/3 cup once cooked) and 2 cups for leafy vegetables. It’s not actually as much as you think!

Most studies categorize vegetable and fruit consumption by weight (hence the 800 grams of fruits and vegetables discussed above), and if they draw an equivalency to servings, it’s typically either 85 grams or 100 grams per serving without differentiating between vegetables and fruit. But, the way a vegetable or fruit serving is standardized in dietary guidelines has shifted in the last decade. Dietary guidelines across the globe have moved away from defining a serving based on weight and towards volume-based measurements.

The reason for this shift is simply, practicality. Most of us, when eating or cooking, intuitively consider volume measurements. We put a spoonful of spices in, we eat by the spoonful or fork-full, and we generally consume all food and drink by volume, not weight. Plus, volume measurements also have a helpful visual aspect to them. For example, 1 cup can be approximated to the size of a fist. Therefore two cups is approximately two fists. A tablespoon is a similar volume to the top half of a thumb.

So, what is a serving for fruits and veggies? It’s standardized to:

- 1 cup for most vegetables and fruit, measured raw

- 2 cups for leafy vegetables, measured raw

- 1/4 cup for fatty fruits (like olives, avocado or coconut)

The weight of the above volume-based servings depends on the exact density of the veggie or fruit in question, but it’s around 100 grams for typical non-starchy veggies, 150 grams for typical root veggies and fruit, 75 grams for typical leafy greens and mushrooms, 50 grams for fatty fruits, and all with quite a lot of variability. For example, 1 cup of grapefruit segments typically weights 230 grams but one cup of orange segments only weighs 131 grams!

Additionally, depending on the water content and density of the fruit or veggie we’re talking about, and depending on the cooking method, most will lose between a third to about half of their volume when cooked. But, again, there’s a lot of variability. As an extreme example, it takes about 3 1/2 cups of raw spinach (nearly 2 servings) to yield 1/2 cup cooked, but boiling 1 cup of Brussels sprouts will yield 3/4 cups! So we can’t always to say one serving is 1/2 cup cooked; although, this is still a pretty good assumption on average.

All this to say, approximations are just fine and we don’t need to weigh and measure our vegetables to stay on track. We can reasonably approximate the goal of 500 to 600 grams of veggies daily to 5 to 8 servings, a serving being 1 cup (or a fist) if raw, and 1/2 cup (or half a fist) if cooked. And, we can approximate the goal of 300 grams of fruit daily to 2 or 3 servings, a serving being 1 cup (or a fist) if raw and 1/2 cup (or half a fist) if cooked. And, if you’re interested in being more precise, all the information you need can be found in the Nutrient Facts section of this website!

Serving Sizes

Serving sizes aren’t as big as you think! Here’s a handy dandy cheat sheet with the serving size and visual approximation for each food.

Frozen and Canned Options Are Great!

What if you don’t have access to, or can’t afford, to eat this many fresh fruits and vegetables? Frozen and canned are great options!

Frozen veggies and fruit can even be more nutrient-dense than fresh! Not only are they picked at peak ripeness, which maximizes nutrient density, but they’re frozen quickly which helps to preserve all their valuable vitamins, minerals and antioxidants. Some fruits and vegetables are more prone to nutrient loss through storage than others, and vegetables especially sensitive to loss of antioxidant activity include cucumber, zucchini, broccoli, Brussels sprouts and leeks. These are the veggies that it’s most important to consume as fresh as possible, by shopping at your local Farmer’s Market and by eating them as soon as possible after purchase. But, these vegetables are still great choices, even if they aren’t freshly picked. And, a great way to maximize the benefits of these veggies, while saving money, is to buy frozen!

Canned foods are convenient, inexpensive alternatives to fresh and frozen foods. Unfortunately, canned foods have been maligned in the health and wellness sphere as having inferior nutrition and flavor. So, let’s bust that myth! When we actually crunch the numbers, we see that canning has a minimal impact on nutrient density, comparing to other cooking techniques, across food groups. (Use the Nutrivore Score Search to look them up and see for yourself!) In addition, BPA is being phased out of can liners and only about 10% of canned goods in the U.S.A. still contain BPA, making it extremely likely that your BPA exposure will stay well below the level scientific studies show can be harmful to health, even if you consume lots of canned foods. So, don’t feel guilty about buying canned foods! Most of the time, opt for canned foods without added sugars (this does lower the nutrient density) or really high levels of sodium (to make it easier to keep sodium intake moderate)—noting of course that there are no bad foods on Nutrivore and every food can have a place in a healthy diet.

Easily track your servings of Nutrivore Foundational Foods!

The Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

The Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix digital resource is an easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist designed to help you maximize nutrient-density and meet serving suggestions of Nutrivore foundational foods, all without having to weigh or measure your foods!

Includes a 22-page instructional guide and downloadable interactive guides.

Buy now for instant digital access.

Don’t Like Vegetables? Read This!

Positive associations and familiarity are major drivers of food preference.

This might be a great time to emphasize that it takes only a few weeks for our taste buds to adapt to big shifts in our diets. Studies looking at taste adaptation to one of a low-sugar, low-salt, or low-fat diet have shown that over the course of a few weeks (4 to 12, depending on the study), participants develop a preference for the healthier foods they’ve been eating. This is attributable to our taste buds becoming more sensitive.

Food familiarity and flavor association with positive experiences (e.g., feeling good physically, the food tasting good, or eating in a positive social environment) is another key driver of food preference. Studies show that with repeated exposure to foods that we innately dislike, we can not only lose our aversions to those foods but actually develop a preference for them. In fact, we can learn to like new flavors after trying them as few as four or five times. What does this mean? If you aren’t enjoying the new healthy foods you’re adding to your diet, don’t give up! The more of these healthy foods you eat, the more you’ll enjoy them!

Another way to increase adaptation to new foods is to pair them with foods you love. A 2014 study looked at ways to increase children’s liking and willingness to consume Brussels sprouts through associative learning. Basically, that means they investigated whether they could get kids to eat more Brussels sprouts by repeatedly pairing them with nutrients or flavors that the children liked. Specifically, they looked at the impact of pairing veggies with sweetened and unsweetened cream cheese as compared to repeated exposure to plain veggies in increasing how much the children (aged 3 to 5 years) liked and ate bitter and non-bitter veggies. One group of kids were given Brussels sprouts (bitter) with sweetened cream cheese and cauliflower (non-bitter) with unsweetened cream cheese, the second group received the reverse pairing, and a third group were given veggies with no cream cheese. The results showed that pairing Brussels sprouts with cream cheese increased liking and consumption more than exposure. Less than 25% of children liked the sprouts alone but 72% liked sprouts with cream cheese, while mere exposure to sprouts was not successful at all as 80% of children given the sprouts plain still disliked them afterwards. On the other hand, cauliflower was liked by all groups regardless of cream cheese. Overall, the study showed the best way to increase the children’s liking of a new bitter veggie was by pairing it with a nutrient/flavor they liked. What does this mean for you? If you’re not a Brussels fan (or any other nutrient-dense food), try pairing them with one of your favorite foods or with a dip or dressing that you like. In no time at all, you may be looking forward to eating this nutrient dense veggie.

In addition, every little bit counts! In fact, the magnitude of benefit is much higher going from no veggies to 200 grams daily compared to going from 600 to 800 grams daily. So, if 5 servings per day is feeling overwhelming, it’s okay to break that down into iterative goals. And, a great place to start is simply to eat a little bit more vegetables every day than you currently consume!

Take-Home Message

The single most impactful dietary pattern on health is consuming a wide range of vegetables and fruits, and plenty of them! Ideally, aim for 5 or more servings of vegetables daily, and 2 to 3 servings of fruit. It’s okay to work up to this goal! And, the more variety you choose, not only is that even better for your health, but also the easier it will be to meet these serving goals!

The Best Support to Build This Important Daily Habit!

Nutrivore Salad-a-Day Challenge

The Nutrivore Salad-a-Day Challenge e-book explains all the ways a daily salad can improve your health, plus includes a collection of 10 handy visual guides and food lists, like the Nutrivore Salad Matrix.

Plus, you’ll find 50+ recipes, including over 30 of our favorite salad recipes plus recipes for delicious dressings and tasty toppers.

Buy now for instant digital access.

Citations

Expand to see all scientific references for this article.

Almeida S, Raposo A, Almeida-González M, Carrascosa C. Bisphenol A: Food Exposure and Impact on Human Health. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2018 Nov;17(6):1503-1517. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12388.

Aune D, Giovannucci E, Boffetta P, Fadnes LT, Keum N, Norat T, Greenwood DC, Riboli E, Vatten LJ, Tonstad S. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality-a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2017 Jun 1;46(3):1029-1056. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw319.

Blumfield M, Mayr H, De Vlieger N, Abbott K, Starck C, Fayet-Moore F, Marshall S. Should We ‘Eat a Rainbow’? An Umbrella Review of the Health Effects of Colorful Bioactive Pigments in Fruits and Vegetables. Molecules. 2022 Jun 24;27(13):4061. doi: 10.3390/molecules27134061.

Capaldi-Phillips ED, Wadhera D. Associative conditioning can increase liking for and consumption of brussels sprouts in children aged 3 to 5 years. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014 Aug;114(8):1236-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.11.014.

Howe S.R., Borodinsky L., Lyon R.S. Potential exposure to bisphenol A from food-contact use of epoxy coated cans. J. Coat. Technol. 1998;70:69–74.

McDonald D, Hyde E, Debelius JW, Morton JT, Gonzalez A, Ackermann G, Aksenov AA, Behsaz B, Brennan C, Chen Y, DeRight Goldasich L, Dorrestein PC, Dunn RR, Fahimipour AK, Gaffney J, Gilbert JA, Gogul G, Green JL, Hugenholtz P, Humphrey G, Huttenhower C, Jackson MA, Janssen S, Jeste DV, Jiang L, Kelley ST, Knights D, Kosciolek T, Ladau J, Leach J, Marotz C, Meleshko D, Melnik AV, Metcalf JL, Mohimani H, Montassier E, Navas-Molina J, Nguyen TT, Peddada S, Pevzner P, Pollard KS, Rahnavard G, Robbins-Pianka A, Sangwan N, Shorenstein J, Smarr L, Song SJ, Spector T, Swafford AD, Thackray VG, Thompson LR, Tripathi A, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Vrbanac A, Wischmeyer P, Wolfe E, Zhu Q; American Gut Consortium, Knight R. American Gut: an Open Platform for Citizen Science Microbiome Research. mSystems. 2018 May 15;3(3):e00031-18. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00031-18.

Murcia, Ma & Jiménez, Antonia & Martínez-Tomé, Magdalena. Vegetables antioxidant losses during industrial processing and refrigerated storage. Food Research International. 2009 42. 1046-1052. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2009.04.012.

Oude Griep LM, Verschuren WM, Kromhout D, Ocké MC, Geleijnse JM. Variety in fruit and vegetable consumption and 10-year incidence of CHD and stroke. Public Health Nutr. 2012 Dec;15(12):2280-6. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012000912.

Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G, Lampousi AM, Knüppel S, Iqbal K, Bechthold A, Schlesinger S, Boeing H. Food groups and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017 Jun;105(6):1462-1473. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.153148.

Wallace TC, Bailey RL, Blumberg JB, Burton-Freeman B, Chen CO, Crowe-White KM, Drewnowski A, Hooshmand S, Johnson E, Lewis R, Murray R, Shapses SA, Wang DD. Fruits, vegetables, and health: A comprehensive narrative, umbrella review of the science and recommendations for enhanced public policy to improve intake. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;60(13):2174-2211. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1632258.