Key Takeaways (expand)

- Vitamin B12, or cobalamin, has the biggest and most complex chemical structure out of any vitamin.

- Although a number of compounds are technically cobalamins, only two forms are used by the human body: methylcobalamin, and 5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin.

- Vitamin B12 serves as a cofactor for the enzymes methionine synthase (which requires B12 in the form of methylcobalamin), and L-methylmalonyl-coenzyme A mutase (which requires B12 in the form of 5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin).

- Vitamin B12 is a cofactor for methionine synthase, giving it a critical role in the creation of methionine from homocysteine.

- Like other B vitamins, vitamin B12 is involved in energy metabolism; its specific role is in synthesizing an important intermediate called succinyl CoA, which allows some branched-chain amino acids and fatty acids to enter the cycle.

- Vitamin B12 is also needed for hemoglobin synthesis and red blood cell production, as well as for the metabolism of folate

- Although vitamin B12 is able to lower levels of homocysteine (a cardiovascular risk factor), studies haven’t found a notable protective effect of this vitamin on actual heart disease risk or stroke.

- Some research has linked low vitamin B12 levels to a greater risk of cancer, as well as chromosome breakage (a cancer risk marker); this may be due to vitamin B12’s role in folate metabolism, with folate being needed for preventing the DNA damage associated with cancer.

- Vitamin B12 plays a role in synthesizing neurotransmitters and preserving the myelin sheath surrounding neurons, giving it a role in maintaining neurological health.

- Vitamin B12 may be protective against dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, possibly through its effects on homocysteine (with elevated levels being linked to higher risk of these conditions, as well as to lower cognitive function scores in the elderly); Alzheimer’s patients also have disproportionately high rates of vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Patients with depression tend to have higher rates of B12 deficiency, and studies have linked low levels of vitamin B12 with greater risk of depression during pregnancy.

- Vitamin B12 deficiency can occur due to long-term insufficient intake (including from unsupplemented vegan or vegetarian diets) or from conditions that inhibit absorption (such as celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, or pernicious anemia—where the body lacks a protein called intrinsic factor that’s needed to bind and absorb vitamin B12 in the small intestine).

- When it occurs, vitamin B12 deficiency can produce neurologic symptoms (sometimes permanent) like numbness and tingling in the feet and hands, difficulty walking, memory loss, and dementia, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms like appetite loss, diarrhea, loss of bladder control, and constipation.

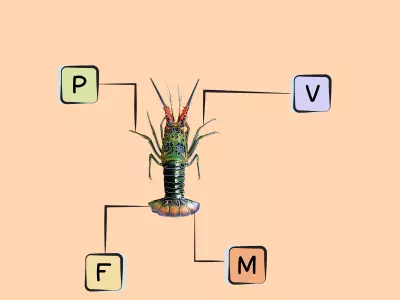

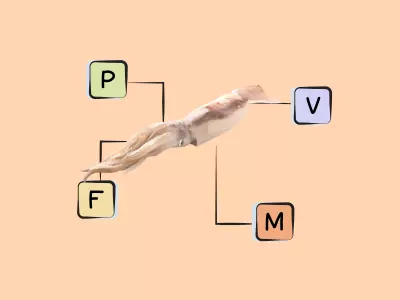

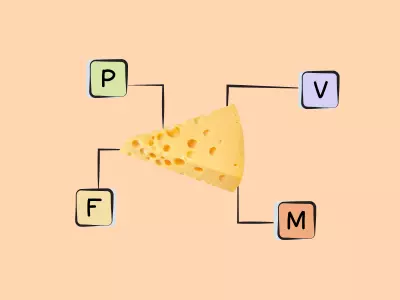

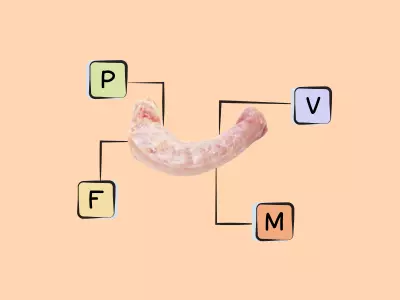

- Vitamin B12 is manufactured exclusively by microorganisms, so the best sources of vitamin B12 are animal foods that concentrate bacterially produced B12 in their cells (particularly fish, shellfish, organ meat, beef, eggs, poultry, and dairy products); some fermented soy products like tempeh also contain vitamin B12.

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

- The Biological Roles of Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 in Health and Disease+−

- Vitamin B12 and Cardiovascular Disease

- Vitamin B12 and Cancer

- Vitamin B12 and Pregnancy

- Vitamin B12 and Neurodegenerative Disease

- Vitamin B12 and Depression

- Vitamin B12 and Type 2 Diabetes

- Vitamin B12 and Sleep

- Vitamin B12 and Sarcopenia

- Vitamin B12 and Fatigue

- Vitamin B12 and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

- Vitamin B12 and Pain

- Vitamin B12 and Vitiligo

- Vitamin B12 and Fingernail Problems

- Vitamin B12 and Migraine

- Health Effects of Vitamin B12 Deficiency

- How Much Vitamin B12 Do We Need?

- Best Food Sources of Vitamin B12

- Good Food Sources of Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12, also called cobalamin, is a water-soluble nutrient with the biggest and most complex chemical structure out of any vitamin! It’s the only vitamin to contain a metal ion (cobalt), a fact that lent itself to the vitamin’s name (cobalamin being a combination of the words cobalt and vitamin). It took over 100 years for the deficiency effects of this nutrient to be discovered and fully understood, with chemists first officially isolating vitamin B12 in 1948. And, research on its role in disease prevention is still ongoing today!

Although a number of compounds are technically cobalamins, the human body only uses two forms: methylcobalamin, and 5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin. (Many nutritional supplements contain vitamin B12 in the form of cyanocobalamin, but our bodies readily convert this into the two forms we can use.)

Like other B vitamins, vitamin B12 is involved in energy metabolism and red blood cell production, but it also plays a major role in DNA synthesis, nervous system health, and the metabolism of another B vitamin: folate.

Because vitamin B12 is manufactured exclusively by microorganisms, the best sources of vitamin B12 are animal foods that concentrate bacterially produced B12 in their cells—such as fish (especially sardines, salmon, tuna, and cod), shellfish such as shrimp and scallops, organ meat, beef, eggs, poultry, and dairy products. Some fermented soy products like tempeh also contain vitamin B12. Although non-fermented plant foods don’t contain vitamin B12, fortified products such as nutritional yeast, breakfast cereals, and plant-based meat and dairy substitutes (like plant milks) can also supply vitamin B12.

Want to know the top 25 foods for this awesome nutrient?

The Top 25 Foods for Every Nutrient

The Top 25 Foods for Every Nutrient e-book is a well-organized, easy-to-use, grocery store-friendly guide to help you choose foods that fit your needs of 43 important nutrients while creating a balanced nutrient-dense diet.

Get two “Top 25” food lists for each nutrient, plus you’ll find RDA charts for everyone, informative visuals, fun facts, serving sizes and the 58 foods that are Nutrient Super Stars!

Buy now for instant digital access.

The Biological Roles of Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 serves as a cofactor for two enzymes: methionine synthase (which requires B12 in the form of methylcobalamin), and L-methylmalonyl-coenzyme A mutase (which requires B12 in the form of 5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin). As a methionine synthase cofactor, vitamin B12 helps create the amino acid methionine from homocysteine; methionine is then used to synthesize an important methyl group donor called S-adenosylmethoinine (SAM), which is needed for methylation reactions involving DNA, RNA, proteins, and more. When methionine synthase isn’t functioning sufficiently, it can lead to excess homocysteine accumulation (potentially increasing cardiovascular disease risk), as well as aberrant DNA and protein methylation (leading to altered gene expression and chromatin structure, characteristic of cancer cells).

Meanwhile, in the form of a L-methylmalonyl-coenzyme A mutase cofactor, vitamin B12 helps catalyze the conversion of L-methylmalonyl-coenzyme A to succinyl-coenzyme A (succinyl-CoA). In turn, succinyl-CoA is needed for lipid metabolism, protein metabolism, hemoglobin synthesis.

As a result of these enzyme functions, vitamin B12 is also vital for maintaining cardiovascular, brain, and nervous system health. And, along with folate, vitamin B12 is important for metabolizing homocysteine, an amino acid that’s been linked to cardiovascular disease risk when its levels in the blood are elevated.

Like other B vitamins, it also plays an important role in energy metabolism—particularly the second stage of cellular respiration, called the Krebs cycle or citric acid cycle. The Krebs cycle is an incredibly important series of chemical reactions that all aerobic organisms use to generate energy, through an eight-step process taking place in a cell’s mitochondria. During this cycle, acetate (in the form of acetyl CoA) derived from carbohydrates, fat, or protein undergoes a series of redox, dehydration, hydration, and decarboxylation reactions to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy currency for all cells—as well as the waste product carbon dioxide, and reduced forms of NADH and FADH2 (which can then be converted into yet more ATP in the last step of the Krebs cycle: oxidative phosphorylation in the electron transport chain). This is complex biochemistry, but the important part here is that there are a whole lot of chemical reactions required to produce energy for our cells, and B vitamins are essential for that process!

Vitamin B12’s specific role in the Krebs cycle is in synthesizing an important intermediate, succinyl CoA, which is catalyzed from methylmalonyl CoA via the B12-dependent enzyme methylmalonyl-coenzyme A mutase. In turn, succinyl CoA allows some branched chain amino acids (valine and isoleucine), propionate, and odd-chain fatty acids to enter the cycle.

Nutrivore Is a Game-Changer—These 5 Free Guides Show You Why

Sign up for the free weekly Nutrivore Newsletter and get 5 high-value downloads—delivered straight to your inbox—that make healthy eating simple and sustainable.

Vitamin B12 in Health and Disease

Vitamin B12 plays a potential role in protecting against some diseases, although in most cases, the current evidence is too mixed (or unavailable!) to be able to say anything conclusive. Research suggests vitamin B12 could be protective against dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and depression, possibly via its effects on homocysteine levels and neurotransmitter production. However, trials in humans have generally used a mixture of B vitamins rather than vitamin B12 in isolation when studying these conditions, making the individual health effects of vitamin B12 unclear. It’s also shown interesting links with cancer, with low vitamin B12 rates potentially impairing folate metabolism and leading to a reduced ability for the body to repair DNA damage (a cancer risk factor).

Vitamin B12 and Cardiovascular Disease

Vitamin B12’s homocysteine-lowering abilities (confirmed both mechanistically and in controlled trials) gives us reason to believe this vitamin could benefit cardiovascular health. But, studies have failed to find a protective effect of vitamin B12 supplementation on heart disease risk, and only combinations of B vitamins (rather than vitamin B12 alone) have demonstrated a protective effect for stroke—making it unclear how much of a role vitamin B12 itself plays.

Vitamin B12 and Cancer

Some (but not all!) observational studies have also shown that low vitamin B12 status is associated with a greater risk of cancer, as well as cancer risk markers like chromosome breakage. Because vitamin B12 is needed for folate metabolism, a shortage of vitamin B12 can keep folate trapped in an inactive form, ultimately impairing DNA synthesis and methylation (both of which are needed to prevent the DNA damage associated with cancer).

Some observational studies have found that women in the lowest quintile of serum vitamin B12 had a more-than-doubled risk of developing breast cancer compared to women in the four higher quintiles, suggesting a threshold effect (meaning low levels increase risk, but there might not be an additive protective effect of higher levels). One study found a similar trend for vitamin B12 intake, with women ingesting the least B12 having a significantly higher risk of breast cancer than those ingesting the most B12 (this trend was particularly dramatic among postmenopausal women).

But, not all studies have supported these associations, and more research is needed to get a clearer picture—especially well-designed studies that can control for factors that influence breast cancer risk, like alcohol intake, ethnicity, and menopausal status.

Vitamin B12 and Pregnancy

As with folate, low vitamin B12 status during pregnancy has been linked with a higher risk of neural tube defects. But, while folate supplementation has been clearly shown to help reduce this risk, the jury is still out about whether vitamin B12 supplementation can do the same; studies haven’t documented the effects of vitamin B12 supplementation for neural tube prevention purposes.

Vitamin B12 and Neurodegenerative Disease

Due to its role in preserving the myelin sheath that surrounds neurons, as well as in synthesizing neurotransmitters, vitamin B12 is involved in maintaining neurological health. This includes a potential protective effect for conditions like dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

In fact, Alzheimer’s patients have frequently been shown to be vitamin B12 deficient, and vitamin B12 deficiency could very plausibly contribute to a number of features of dementia (including excess homocysteine and methylmalonic acid accumulation). In observational studies, high homocysteine levels (again, a potential consequence of vitamin B12 deficiency) lead to a significantly higher risk of developing dementia or Alzheimer’s disease over time (for example, compared to people with lower levels, those with plasma homocysteine exceeding 14 μmol/L had over twice the risk of getting Alzheimer’s disease over the span of a decade). Elevated homocysteine has also been linked with significantly lower cognitive function scores in the elderly—though it’s hard to say how much vitamin B12 itself is involved in that trend. And, studies using highly sensitive biomarkers of vitamin B12 status (including methylmalonic acid and holo-transcobalamin, a vitamin B12 carrier) have generally shown that low vitamin B12 status correlates with more rapid cognitive decline and greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

That being said, actual trials showing benefit for B-vitamin supplementation on cognitive decline have generally used multiple B vitamins, not vitamin B12 alone—making it hard to distill the effects of vitamin B12 versus other nutrients like folate and vitamin B6, which also play a neuroprotective role.

Vitamin B12 and Depression

Vitamin B12 has a compelling relationship with depression. Across studies, a disproportionate number of patients suffering from depression have been shown to have low levels of vitamin B12—possibly due to vitamin B12 deficiency inhibiting the methylation reactions orchestrated by S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), in turn impacting affecting depression-linked neurotransmitters. (Indeed, some studies have shown that supplementing with SAM is able to improve symptoms of depression!) Observational research has even linked low levels of vitamin B12 with greater risk of depression during pregnancy, even after controlling for potential confounders.

However, as with dementia and cognitive decline, trials testing the effects of vitamin B12 on depression have also included other B vitamins (especially folate and vitamin B6), so more research is needed to understand the effects of vitamin B12 specifically.

Vitamin B12 and Type 2 Diabetes

Research suggests a link between vitamin B12 and type 2 diabetes, as well as some complications of diabetes. For example, observational studies show that type 2 diabetics have a relatively high prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency. However, this relationship is confounded by the fact that a common diabetes medication (metformin) tends to lower the absorption of vitamin B12 in the small intestine, in turn inducing deficiency. Whether vitamin B12 deficiency causally contributes to diabetes has yet to be determined!

More compelling research suggests that vitamin B12 could be helpful in treating diabetic neuropathy, a type of nerve damaged caused by diabetes (especially long-term, poorly managed diabetes). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of patients with diabetic neuropathy found that supplementation with 1 mg of oral vitamin B12 (methylcobalamin) daily for twelve months improved all neurophysiological parameters, autonomic nervous system control, pain scores, and quality of life. A 2022 meta-analysis reached similar findings, showing that among type 2 diabetics with neuropathy, vitamin B12 can improve neuropathic symptoms and reduce pain.

Vitamin B12 and Sleep

Vitamin B12 may be associated with some sleep disorders and overall sleep quality. A 2023 cross-sectional study found that lower vitamin B12 levels were associated with insomnia among female, elderly, and non-obese participants, while lower vitamin B12 levels were associated with excessive daytime sleepiness among obese participants. A 2021 analysis of female college students similarly showed that those with higher blood levels of vitamin B12 reported better sleep quality scores and lower use of sleep medication. Several intervention studies, mostly small and preliminary, have also suggested that oral vitamin B12 (either as methylcobalamin or cyanocobalamin) can directly influence melatonin secretion, positively impact the circadian cycle, and help correct sleep-wake rhythm disorders.

Vitamin B12 and Sarcopenia

Some research suggests vitamin B12 could be related to sarcopenia—age-related loss of muscle and strength. A 2017 study of 403 elderly patients found that compared to those with higher vitamin B12 levels, those with levels under 400 pg/mL had significantly higher incidence of sarcopenia, lower lean body mass, and lower total skeletal mass. A two-year longitudinal study of 926 community-dwelling older adults similarly found that low vitamin B12 levels (under 350 pg/mL) at the beginning of the study tended to increase the incidence of sarcopenia among female, but not male, participants.

It’s worth noting, however, that these findings could be confounded by another dietary factor: protein intake. Along with promoting muscle mass retention, protein-rich animal foods are our main dietary sources of vitamin B12. So, it’s possible that lower vitamin B12 levels among sarcopenic adults are actually a proxy for lower protein intake. More research is needed to determine whether this is the case!

Vitamin B12 and Fatigue

Given its role in energy production, it may not be surprising that vitamin B12 is implicated in fatigue! Specifically, low levels of vitamin B12 can contribute to diminished energy and exercise tolerance, as well as shortness of breath and feelings of overall fatigue. And, some small older trials of vitamin B12 supplementation indicated this nutrient could improve feelings of tiredness. For example, a 1973 double-blind crossover trial of people complaining of tiredness found that vitamin B12 injections (5 mg twice per week for two weeks) significantly improved symptoms.

A 2022 study of patients with fibromyalgia found a significant relationship between vitamin B12 deficiency and fatigue levels; similar findings have appeared for low vitamin B12 levels and fatigue following certain types of stroke.

Vitamin B12 and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Some intriguing research points to certain instances of obsessive-compulsive disorder being an early manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency, although these findings are mostly limited to case studies. A systematic review and meta-analysis from 2022 also found that vitamin B12 levels were significantly lower in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder than in healthy controls. More research is needed to help clarify this relationship!

Vitamin B12 and Pain

Vitamin B12 has been investigated as both a direct and adjunctive treatment for pain. Animal models show that vitamin B12 may exert anti-pain effects through the regeneration of nerves, as well as through the inhibition of several pain-signaling pathways. Animal studies also demonstrate synergistic effects of vitamin B12 in combination with pain medications, including opiates and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

In humans, vitamin B12 has shown efficacy for treating a variety of types of pain, including back pain, spine pain, musculoskeletal pain, abdominal pain, Alzheimer’s disease-related pain, pain ailments resulting from cancer, pain from eye diseases, and neuralgia (pain caused by injured nerves). For example, a 2000 randomized, placebo-controlled, double blind clinical study found that even among patients without vitamin B12 deficiency, intramuscular vitamin B12 was able to significantly decrease lower back pain and pain medication use!

However, more high-quality, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials are still needed to explore the effects of vitamin B12, at different doses and administration routes, on various types of pain.

Vitamin B12 and Vitiligo

Vitiligo is a condition involving the loss of skin color in patches. Studies show that vitamin B12 deficiency is a significant risk factor for vitiligo, with patients frequently exhibiting low blood levels of this nutrient. And, some trials have shown that treatment with vitamin B12, sometimes along with other nutrients, induces repigmentation of the skin. For example, a 1997 clinical trial found that oral treatment with vitamin B12 and folic acid, in combination with sun exposure, stopped the spread of vitiligo in 64% of patients.

Vitamin B12 and Fingernail Problems

Vitamin B12 could influence fingernail health, with deficiency sometimes resulting in melanonychia—brown or black discoloration of the nail. Although rare, this manifestation of insufficient B12 is reversible with supplementation.

Vitamin B12 and Migraine

Vitamin B12 serves as a cofactor in biochemical pathways that may help mitigate migraine symptoms, including those involved in nitric oxide and homocysteine. People who experience migraines have been shown to have significantly lower blood levels of vitamin B12 than people who don’t get migraines. Some trials have also found that vitamin B12 (in conjunction with other B vitamins) is effective for helping prevent migraines, though it’s hard to say what effects are owed to vitamin B12 specifically!

Didn’t know vitamin B12 was this amazing? Maybe your friends will enjoy this too!

Health Effects of Vitamin B12 Deficiency

Because the body has a very high storage capacity for vitamin B12 and a slow daily turnover, true vitamin B12 deficiency is relatively uncommon. But, it can develop from long-term insufficient intake (such as from unsupplemented vegetarian or vegan diets) or, more often, from conditions that inhibit absorption. For example, vitamin B12 deficiency can result from an autoimmune malabsorption syndrome called pernicious anemia, in which the body lacks a protein called intrinsic factor (IF) that’s needed to bind and absorb vitamin B12 in the small intestine. This disorder involves a long-term destruction of cells that line the stomach, and requires treatment with vitamin B12 injections (since the body lacks the protein necessary to obtain vitamin B12 from digestion). Another disorder, food-bound vitamin B12 malabsorption, inhibits the absorption of vitamin B12 that’s bound to food or protein—usually as a result of chronic stomach inflammation, which damages stomach glands and reduces gastric acid production (in turn limiting the amount of vitamin B12 that can be freed from the proteins in food). But, in this case, individuals can still absorb vitamin B12 in its free (unbound) form, and can be treated with vitamin B12 supplements. Both of these conditions tend to be more common in older people (generally over the age of 60), due to digestive dysfunctions associated with age. In addition, infection with the H. pylori bacteria, which leads to stomach inflammation (and sometimes progresses to peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer, or atrophic gastritis), causes reduced vitamin B12 levels in the blood; treating the infection has been shown to subsequently improve vitamin B12 status.

Additional causes of vitamin B12 deficiency include health conditions affecting nutrient absorption (such as celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and tropical sprue), surgical resectioning of the stomach or small intestine, pancreatic insufficiency, alcoholism (which leads to reduced intestinal absorption of vitamin B12), and long-term use of drugs that reduce stomach acid. And, several rare inherited conditions can affect vitamin B12 metabolism, such as Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome (which causes B12 malabsorption) and hereditary intrinsic factor deficiency (also known as congenital pernicious anemia).

Certain medications can interfere with vitamin B12 absorption. These include proton-pump inhibitors (like omeprazole or lansoprazole), histamine-2 receptor antagonists often used for treating peptic ulcers (like cimetidine, famotidine, and ranitidine), and metformin (a common diabetes drug).

Even before physical symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency manifest, deficiency can show up in tests as high blood levels of homocysteine or methylmalonic acid. Left untreated, vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to a number of damaging health effects. These include neurologic symptoms (sometimes permanent) like numbness and tingling in the feet and hands, difficulty walking, absent reflexes, disorientation, memory loss, nerve damage, and dementia, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms like appetite loss (and subsequent weight loss), sore tongue, diarrhea, loss of bladder control, and constipation. These gastrointestinal symptoms are believed to be caused by defective DNA synthesis, which inhibits replication in tissues that have high cell turnover, such as in the GI tract. In children, vitamin B12 deficiency can have symptoms including regression, low muscle tone and strength, involuntary movements, irritability, and developmental delay.

Both severe folate deficiency and vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to megaloblastic anemia—a form of anemia where the bone marrow produces big, underdeveloped red blood cells due to impaired DNA synthesis and reduced nuclear division. As the anemia progresses, it leads to impaired oxygen carrying capacity within the blood, causing symptoms such as fatigue, pale mucus membranes and palms, weakness, and shortness of breath. Because both folate and vitamin B12 deficiency can cause megaloblastic anemia, and the symptoms in both cases are identical, it’s important to correct the condition with the right nutrient: improperly treating B12-induced anemia with high doses of folate can perpetuate the vitamin B12 deficiency, potentially leading to irreversible brain damage.

Everything You Need to Jump into Nutrivore TODAY!

Nutrivore Quickstart Guide

The Nutrivore Quickstart Guide e-book explains why and how to eat a Nutrivore diet, introduces the Nutrivore Score, gives a comprehensive tour of the full range of essential and important nutrients!

Plus, you’ll find the Top 100 Nutrivore Score Foods, analysis of food groups, practical tips to increase the nutrient density of your diet, and look-up tables for the Nutrivore Score of over 700 foods.

Buy now for instant digital access.

How Much Vitamin B12 Do We Need?

The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for vitamin B12 is 2.4 micrograms per day for adults (2.6 micrograms when pregnant and 2.8 micrograms daily when breastfeeding); after the age of 50, adults are advised to obtain some vitamin B12 from supplements or fortified foods, due to the increased risk of food-bound B12 malabsorption. Individuals following strict vegetarian diets, or who otherwise consume diets low in animal products, should regularly consume fortified food sources of vitamin B12 or supplements (although no official recommendations exist here, 25 to 100 micrograms daily of sublingual vitamin B12, or 1000 to 2500 micrograms several times per week, is common).

Individuals with pernicious anemia should seek medical advice from their healthcare provider, since neither food sources nor oral supplements will deliver enough vitamin B12 to meet the body’s needs. Due to vitamin B12’s low toxicity, no tolerable upper intake level has been set. In fact, oral doses as high as 2000 micrograms daily have been used without any significant side effects!

Although vitamin B12 has extremely low toxicity, it’s worth noting that high-dose vitamin B12 supplements—particularly in the form of intramuscular injections—can sometimes cause side effects, including headache, nausea, vomiting, mild diarrhea, itching, skin rash, tiredness, weakness, or tingling in the hands and feet. Vitamin B12 in the form of dietary supplements, including B12-containing multivitamins, are unlikely to produce any noticeable side effects, largely because it’s a water-soluble vitamin and only a fraction of it gets absorbed orally.

| 0 – 6 months | |||||

| 6 months to < 12 months | |||||

| 1 yr – 3 yrs | |||||

| 4 yrs – 8 yrs | |||||

| 9 yrs – 13 yrs | |||||

| 14 yrs – 18 yrs | |||||

| 19 yrs – 50 yrs | |||||

| 51+ yrs | |||||

| Pregnant (14 – 18 yrs) | |||||

| Pregnant (19 – 30 yrs) | |||||

| Pregnant (31 – 50 yrs) | |||||

| Lactating (14 – 18 yrs) | |||||

| Lactating (19 – 30 yrs) | |||||

| Lactating (31 – 50 yrs) |

Nutrient Daily Values

Nutrition requirements and recommended nutrient intake for infants, children, adolescents, adults, mature adults, and pregnant and lactating individuals.

Best Food Sources of Vitamin B12

The following foods have high concentrations of vitamin B12, containing at least 50% of the recommended dietary allowance per serving, making them our best food sources of this valuable B-vitamin!

Want to know the top 500 most nutrient-dense foods?

Top 500 Nutrivore Foods

The Top 500 Nutrivore Foods e-book is an amazing reference deck of the top 500 most nutrient-dense foods according to their Nutrivore Score. Think of it as the go-to resource for a super-nerd, to learn more and better understand which foods stand out, and why!

If you are looking for a quick-reference guide to help enhance your diet with nutrients, and dive into the details of your favorite foods, this book is your one-stop-shop!

Buy now for instant digital access.

Good Food Sources of Vitamin B12

The following foods are also excellent or good sources of vitamin B12, containing at least 10% (and up to 50%) of the daily value per serving.

Ready to Make Healthy Eating Feel Effortless?

Join the FREE 90-day Nutrivore90 Challenge and build lasting habits with no food rules, no guilt—just real progress.

- Weekly downloads, journal prompts, and reflection tools—all completely free.

- Focus on nutrient density, not restriction

- Starts September 1st!

Citations

Expand to see all scientific references for this article.

Afra TP, Razmi TM, Narang T. Reversible Melanonychia Revealing Nutritional Vitamin-B12 Deficiency. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020 Sep 19;11(5):847-848. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_13_20.

Al-Musharaf S, Alabdulaaly A, Bin Mujalli H, Alshehri H, Alajaji H, Bogis R, Alnafisah R, Alfehaid S, Alhodaib H, Murphy AM, Hussain SD, Sabico S, McTernan PG, Al-Daghri N. Sleep Quality Is Associated with Vitamin B12 Status in Female Arab Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Apr 25;18(9):4548. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094548.

Almeida OP, Marsh K, Alfonso H, Flicker L, Davis TM, Hankey GJ. B-vitamins reduce the long-term risk of depression after stroke: The VITATOPS-DEP trial. Ann Neurol. 2010 Oct;68(4):503-10. doi: 10.1002/ana.22189.

Alvarez M, Sierra OR, Saavedra G, Moreno S. Vitamin B12 deficiency and diabetic neuropathy in patients taking metformin: a cross-sectional study. Endocr Connect. 2019 Oct 1;8(10):1324-1329. doi: 10.1530/EC-19-0382.

Ates Bulut E, Soysal P, Aydin AE, Dokuzlar O, Kocyigit SE, Isik AT. Vitamin B12 deficiency might be related to sarcopenia in older adults. Exp Gerontol. 2017 Sep;95:136-140. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.05.017.

Bouloukaki I, Lampou M, Raouzaiou KM, Lambraki E, Schiza S, Tsiligianni I. Association of Vitamin B12 Levels with Sleep Quality, Insomnia, and Sleepiness in Adult Primary Healthcare Users in Greece. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 Nov 23;11(23):3026. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11233026.

Brescoll J, Daveluy S. A review of vitamin B12 in dermatology. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015 Feb;16(1):27-33. doi: 10.1007/s40257-014-0107-3.

Bressa GM. S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAMe) as antidepressant: meta-analysis of clinical studies. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1994;154:7-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1994.tb05403.x.

Buesing S, Costa M, Schilling JM, Moeller-Bertram T. Vitamin B12 as a Treatment for Pain. Pain Physician. 2019 Jan;22(1):E45-E52.

Carmel R. Megaloblastic anemias. Curr Opin Hematol. 1994 Mar;1(2):107-12.

Chae SA, Kim HS, Lee JH, Yun DH, Chon J, Yoo MC, Yun Y, Yoo SD, Kim DH, Lee SA, Chung SJ, Soh Y, Won CW. Impact of Vitamin B12 Insufficiency on Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Older Korean Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Nov 26;18(23):12433. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312433.

Choi S, Chon J, Lee SA, Yoo MC, Chung SJ, Shim GY, Soh Y, Won CW. Impact of Vitamin B12 Insufficiency on the Incidence of Sarcopenia in Korean Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Two-Year Longitudinal Study. Nutrients. 2023 Feb 13;15(4):936. doi: 10.3390/nu15040936.

Didangelos T, Karlafti E, Kotzakioulafi E, Margariti E, Giannoulaki P, Batanis G, Tesfaye S, Kantartzis K. Vitamin B12 Supplementation in Diabetic Neuropathy: A 1-Year, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2021 Jan 27;13(2):395. doi: 10.3390/nu13020395.

Douaud G, Refsum H, de Jager CA, Jacoby R, Nichols TE, Smith SM, Smith AD. Preventing Alzheimer’s disease-related gray matter atrophy by B-vitamin treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Jun 4;110(23):9523-8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301816110.

Dror DK, Allen LH. Interventions with vitamins B6, B12 and C in pregnancy. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012 Jul;26 Suppl 1:55-74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01277.x.

Ellis FR, Nasser S. A pilot study of vitamin B12 in the treatment of tiredness. Br J Nutr. 1973 Sep;30(2):277-83. doi: 10.1079/bjn19730033.

Faico-Filho KS, Martins RS, Santos CL, Poles WA, Mello RB, Moura-Faico MM. Total melanonychia of 20 nails as a rare manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. JAAD Case Rep. 2020 Mar 30;6(4):372-373. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.02.014.

Fenech M. Folate (vitamin B9) and vitamin B12 and their function in the maintenance of nuclear and mitochondrial genome integrity. Mutat Res. 2012 May 1;733(1-2):21-33. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.11.003.

Furgała R, Stompor M. Effects of vitamin B12 supplementation on pain relief in certain diseases – a literature review. Acta Biochim Pol. 2022 Apr 22;69(2):265-271. doi: 10.18388/abp.2020_5876.

Green R, Allen LH, Bjørke-Monsen AL, Brito A, Guéant JL, Miller JW, Molloy AM, Nexo E, Stabler S, Toh BH, Ueland PM, Yajnik C. Vitamin B12 deficiency. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017 Jun 29;3:17040. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.40.

Hosseinzadeh H, Moallem SA, Moshiri M, Sarnavazi MS, Etemad L. Anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12) against acute and chronic pain and inflammation in mice. Arzneimittelforschung. 2012 Jul;62(7):324-9. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1311635.

Huang T, Chen Y, Yang B, Yang J, Wahlqvist ML, Li D. Meta-analysis of B vitamin supplementation on plasma homocysteine, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. Clin Nutr. 2012 Aug;31(4):448-54. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2011.01.003.

Huijts M, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Rouhl RP, Menheere P, Duits A. Effects of vitamin B12 supplementation on cognition, depression, and fatigue in patients with lacunar stroke. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013 Mar;25(3):508-10. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212001925.

Institute of Medicine (US) Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and Choline. Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1998.

Juhlin L, Olsson MJ. Improvement of vitiligo after oral treatment with vitamin B12 and folic acid and the importance of sun exposure. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997 Nov;77(6):460-2. doi: 10.2340/000155555577460462.

Karedath J, Batool S, Arshad A, Khalique S, Raja S, Lal B, Anirudh Chunchu V, Hirani S. The Impact of Vitamin B12 Supplementation on Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Diabetic Neuropathy: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cureus. 2022 Nov 22;14(11):e31783. doi: 10.7759/cureus.31783.

Khattab R, Albannawi M, Alhajjmohammed D, Alkubaish Z, Althani R, Altheeb L, Ayoub H, Mutwalli H, Altuwajiry H, Al-Sheikh R, Purayidathil T, Abuzaid O. Metformin-Induced Vitamin B12 Deficiency among Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus’ Patients: A Systematic Review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2023;19(4):e180422203716. doi: 10.2174/1573399818666220418080959.

Kivipelto M, Annerbo S, Hultdin J, Bäckman L, Viitanen M, Fratiglioni L, Lökk J. Homocysteine and holo-transcobalamin and the risk of dementia and Alzheimers disease: a prospective study. Eur J Neurol. 2009 Jul;16(7):808-13. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02590.x.

Kozyraki R, Cases O. Vitamin B12 absorption: mammalian physiology and acquired and inherited disorders. Biochimie. 2013 May;95(5):1002-7. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.11.004.

Kuzminski AM, Del Giacco EJ, Allen RH, Stabler SP, Lindenbaum J. Effective treatment of cobalamin deficiency with oral cobalamin. Blood. 1998 Aug 15;92(4):1191-8.

Martí-Carvajal AJ, Solà I, Lathyris D, Karakitsiou DE, Simancas-Racines D. Homocysteine-lowering interventions for preventing cardiovascular events. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jan 31;(1):CD006612. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006612.pub3.

Mauro GL, Martorana U, Cataldo P, Brancato G, Letizia G. Vitamin B12 in low back pain: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2000 May-Jun;4(3):53-8.

Mayer G, Kröger M, Meier-Ewert K. Effects of vitamin B12 on performance and circadian rhythm in normal subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996 Nov;15(5):456-64. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00055-3.

Miyan Z, Waris N; MIBD. Association of vitamin B12deficiency in people with type 2 diabetes on metformin and without metformin: a multicenter study, Karachi, Pakistan. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020 May;8(1):e001151. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-001151.

Montes LF, Diaz ML, Lajous J, Garcia NJ. Folic acid and vitamin B12 in vitiligo: a nutritional approach. Cutis. 1992 Jul;50(1):39-42.

Munipalli B, Strothers S, Rivera F, Malavet P, Mitri G, Abu Dabrh AM, Dawson NL. Association of Vitamin B12, Vitamin D, and Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone With Fatigue and Neurologic Symptoms in Patients With Fibromyalgia. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2022 Jul 31;6(4):381-387. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2022.06.003.

Nematgorgani S, Razeghi-Jahromi S, Jafari E, Togha M, Rafiee P, Ghorbani Z, Ahmadi ZS, Baigi V. B vitamins and their combination could reduce migraine headaches: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Curr J Neurol. 2022 Apr 4;21(2):105-118. doi: 10.18502/cjn.v21i2.10494.

Ohta T, Ando K, Iwata T, Ozaki N, Kayukawa Y, Terashima M, Okada T, Kasahara Y. Treatment of persistent sleep-wake schedule disorders in adolescents with methylcobalamin (vitamin B12). Sleep. 1991 Oct;14(5):414-8.

Okawa M, Mishima K, Nanami T, Shimizu T, Iijima S, Hishikawa Y, Takahashi K. Vitamin B12 treatment for sleep-wake rhythm disorders. Sleep. 1990 Feb;13(1):15-23. doi: 10.1093/sleep/13.1.15.

Pawlak R, Parrott SJ, Raj S, Cullum-Dugan D, Lucus D. How prevalent is vitamin B(12) deficiency among vegetarians? Nutr Rev. 2013 Feb;71(2):110-7. doi: 10.1111/nure.12001.

Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Fried LP, Allen RH, Stabler SP. Vitamin B(12) deficiency and depression in physically disabled older women: epidemiologic evidence from the Women’s Health and Aging Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000 May;157(5):715-21. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.715.

Peppard L, Oh KM, Gallo S, Milligan R. Risk of depression in pregnant women with low-normal serum Vitamin B12. Res Nurs Health. 2019 Aug;42(4):264-272. doi: 10.1002/nur.21951. Epub 2019 May 22.

Pflipsen MC, Oh RC, Saguil A, Seehusen DA, Seaquist D, Topolski R. The prevalence of vitamin B(12) deficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009 Sep-Oct;22(5):528-34. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.05.090044.

Seshadri S, Beiser A, Selhub J, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, D’Agostino RB, Wilson PW, Wolf PA. Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2002 Feb 14;346(7):476-83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011613.

Togha M, Razeghi Jahromi S, Ghorbani Z, Martami F, Seifishahpar M. Serum Vitamin B12 and Methylmalonic Acid Status in Migraineurs: A Case-Control Study. Headache. 2019 Oct;59(9):1492-1503. doi: 10.1111/head.13618.

Urits I, Yilmaz M, Bahrun E, Merley C, Scoon L, Lassiter G, An D, Orhurhu V, Kaye AD, Viswanath O. Utilization of B12 for the treatment of chronic migraine. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020 Sep;34(3):479-491. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2020.07.009.

Valizadeh M, Valizadeh N. Obsessive compulsive disorder as early manifestation of B12 deficiency. Indian J Psychol Med. 2011 Jul;33(2):203-4. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.92051.

Valuck RJ, Ruscin JM. A case-control study on adverse effects: H2 blocker or proton pump inhibitor use and risk of vitamin B12 deficiency in older adults. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004 Apr;57(4):422-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.08.015.

Vitamin B12: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Dietary Supplements.

Walker JG, Batterham PJ, Mackinnon AJ, Jorm AF, Hickie I, Fenech M, Kljakovic M, Crisp D, Christensen H. Oral folic acid and vitamin B-12 supplementation to prevent cognitive decline in community-dwelling older adults with depressive symptoms–the Beyond Ageing Project: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012 Jan;95(1):194-203. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.007799.

Wang ZP, Shang XX, Zhao ZT. Low maternal vitamin B(12) is a risk factor for neural tube defects: a meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 Apr;25(4):389-94. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.580800.

Yan S, Liu H, Yu Y, Han N, Du W. Changes of Serum Homocysteine and Vitamin B12, but Not Folate Are Correlated With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Front Psychiatry. 2022 May 9;13:754165. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.754165.

Yang D, Baumgartner RN, Slattery ML, Wang C, Giuliano AR, Murtaugh MA, Risendal BC, Byers T, Baumgartner KB. Dietary intake of folate, B-vitamins and methionine and breast cancer risk among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e54495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054495.