Key Takeaways (expand)

- Calcium is the most abundant mineral in the human body, composing up to 2% of our total body weight!

- Along with being a major structural component of bones, calcium helps build dental enamel (the hard outer shell of teeth).

- Calcium also functions as an electrolyte—giving it a role in regulating nerve impulses, muscle contraction, heartbeat, blood clotting, fluid balance, and blood pH.

- Too much or too little calcium in the blood can is harmful (and sometimes fatal!), so the body works hard to keep levels with in very a specific range—mobilizing it out of bone tissue when levels get too low, and altering its absorption and excretion when levels get too high.

- Calcium has important interactions with other nutrients: it’s dependent on vitamin D for proper intestinal absorption, can be excreted in excess when phosphorus intake is too high, and requires magnesium for mobilization to and from bone tissue.

- One of the best-studied benefits of calcium is on bone health: numerous studies show that calcium is protective against osteoporosis, can lower the risk of fractures in older adults (especially when combined with vitamin D), and reduces bone loss following menopause.

- Dietary calcium can also reduce kidney stone formation, due to binding with oxalate (a component of kidney stones) in the intestine and reducing its absorption!

- Calcium can also protect against high blood pressure—especially during pregnancy.

- Many studies have linked calcium intake with lower risk of colorectal cancer, as well as a lower risk of death following colorectal cancer diagnosis.

- As a result of its cell signaling duties, calcium is involved in a number of processes that help support healthy body weight—including insulin secretion, glycogen metabolism, lipolysis (lipid breakdown), fat oxidation, hormone signaling, and appetite regulation.

- There’s some evidence that calcium can make PMS symptoms less severe!

- Although more research is needed, a few studies have linked higher calcium intake with an increased risk of heart attack and prostate cancer—but these associations may be driven by other components of calcium-rich foods (especially dairy).

- Calcium insufficiency can lead to loss of bone density, increased risk of dental decay, and (in children and adolescents) a lack of reaching peak bone mass.

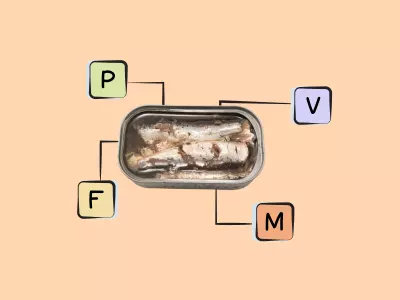

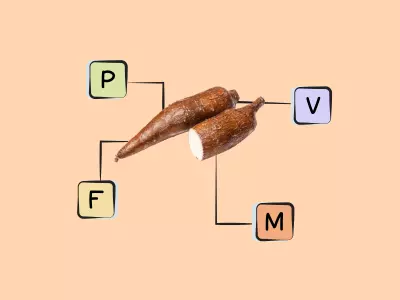

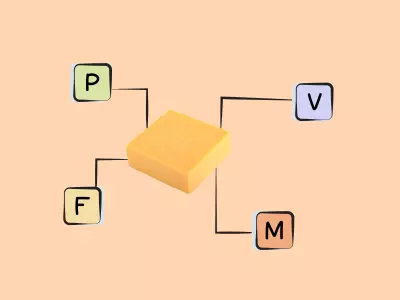

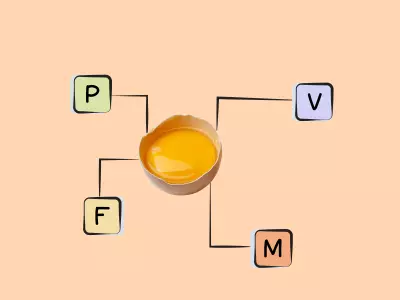

- Great sources of calcium include dairy products (particularly milk, cheese, yogurt, and kefir), bone-in sardines, green vegetables (especially Brassica vegetables like collard greens, kale, bok choy, turnip greens, broccoli, and cabbage), spinach, and seaweed.

Calcium is the most abundant mineral in the human body, composing up to 2% of our total body weight—the vast majority of which is located in our bones and teeth. Along with its famous role in building strong bones, calcium serves as a second messenger in cell-signaling pathways.

Importantly, this nutrient functions as an electrolyte—a class of minerals that dissociate into charged particles (called ions) when dissolved in solution, making them capable of conducting electricity. On the whole, electrolytes help regulate fluid balance within the body, regulate nerve and muscle function (including the heart!), maintain a normal blood pH, and transmit nerve signals!

Calcium was first isolated in 1808 by Sir Humphry Davy (Britain’s leading scientist at the time, and also the inventor of the miner’s safety lamp!), who used electrolysis to isolate calcium from a mixture of lime and mercury oxide. But, humans have been using calcium long before we knew its chemical makeup! The Ancient Romans mixed calcium oxide with water to use as mortar for stone structures, and literature from the 10th century AD references plaster of paris (a mixture of calcium sulphate and dehydrated gypsum) to use for setting broken bones. The word calcium derives from the Latin calx, meaning “lime.”

Along with dairy products (particularly low-fat items), good sources of calcium are bone-in sardines, green vegetables (especially Brassica vegetables like kale, collard greens, turnip greens, bok choy, broccoli, and cabbage), and seaweed. Some other plant foods like spinach, rhubarb, and beans are also relatively rich in calcium, but also contain high levels of oxalate or phytate, which bind to calcium and inhibit its absorption. Other food sources include fortified foods like orange juice, soy milk, and certain cereals.

The Biological Roles of Calcium

Calcium’s two main functions are structural and regulatory: one, supporting skeletal health, and two, helping regulate cellular communication and protein functioning. And, under those two umbrellas are some pretty impressive activities!

Calcium is indispensable for building bone tissue. Along with serving as a major structural component of the skeleton (bone mineral is comprised of calcium phosphate crystals), calcium is a component of dental enamel—the hard outer shell of teeth. Cells called osteoblasts are responsible for depositing calcium to synthesize new bone. Without this mineral, we wouldn’t have the building blocks for the robust inner framework that supports our entire body!

Keeping circulating calcium levels within a very specific range is critical for physiological functioning. So critical, in fact, that the parathyroid hormone (PTH) is in charge of tightly regulating the amount of calcium in our blood, sometimes by “borrowing” calcium from bones (as well as from kidney and intestinal cells) if there’s not enough of it in the blood. More specifically, when the parathyroid glands sense calcium levels dropping, they begin secreting PTH, which stimulates bone resorption (the breakdown of bone tissue to release calcium and other minerals) and prompts the conversion of vitamin D into its active form (which in turn reduces the excretion of calcium and increases its intestinal absorption). Indeed, it’s less dangerous for the body to borrow calcium from skeletal tissue than to let blood calcium levels fall out of range: if the latter happens to an extreme degree, it can be deadly!

The importance of calcium homeostasis is due to the many functions calcium is essential for, particularly when it comes to cell signaling. This mineral helps regulate the constriction and relaxation of blood vessels, nerve impulses, muscle contraction, glycogen metabolism, cellular differentiation and motility, the secretion of hormones like insulin, and coagulation—AKA blood clotting (the binding of calcium ions is needed for activating seven vitamin K-dependent clotting factors). These activities are all controlled by differences in electrochemical signaling inside and outside of cells, as well as the flow through cellular membranes that can change these gradients. And, calcium is required to stabilize many proteins, including enzymes. So, the concentration of calcium in different tissues impacts extremely important functions like communication in the nervous system or contractility of our heart.

What’s more, calcium ions can also be toxic to cells. So, the body has to strike a balance between calcium-mediated cell function and calcium-mediated cell death by not only preventing blood calcium levels from dropping too low, but also preventing them from getting too high. To maintain calcium levels within a healthy upper bound, the thyroid gland begins secreting a peptide hormone called calcitonin as soon as blood calcium concentrations start rising; this hormone then inhibits PTH secretion, increases urinary calcium secretion, and decreases both intestinal calcium absorption and bone resorption.

Interactions with Other Nutrients

Calcium has some important interactions with other nutrients, too. It’s dependent on the active form of vitamin D (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D) for optimal absorption from the intestines, and can be excreted in excess when sodium intake is high (for every gram of sodium excreted by the kidneys, about 26 mg of calcium gets drawn into the urine). However, some trials have found that increasing potassium intake can prevent this sodium-induced calcium loss. Phosphorus, too, increases the urinary excretion of calcium, particularly in diets with low calcium-to-phosphorus ratios or with large quantities of soft drinks containing phosphoric acid. Magnesium deficiency can impair PTH excretion by the parathyroid glands, altering the movement of calcium from bone tissue to blood (and vice versa). Calcium may even interact with the heavy metal lead, acting protectively against lead toxicity by decreasing how much of it gets absorbed in the intestine, and preventing lead from being released from the skeleton during bone demineralization. And, despite the myth that high-protein diets cause a negative calcium balance and can increase bone loss, most studies have actually found that protein enhances intestinal calcium absorption and is either neutral or beneficial for bone health (as measured by bone mineral density and fracture risk).

Drug Interactions with Calcium

Calcium (particularly supplements) can also interact with certain drugs in ways that are important to be aware of. In people taking digoxin, high-dose calcium supplementation can increase the risk of abnormal heart rhythms, and it can also reduce the absorption of bisphosphonates, the beta-blocker sotalol, tetracycline, quinolone antibiotics, and levothyroxine (so, it’s important to take any calcium supplements at least two hours apart from taking these medications!).

Want to know the top 25 foods for this awesome nutrient?

The Top 25 Foods for Every Nutrient

The Top 25 Foods for Every Nutrient e-book is a well-organized, easy-to-use, grocery store-friendly guide to help you choose foods that fit your needs of 43 important nutrients while creating a balanced nutrient-dense diet.

Get two “Top 25” food lists for each nutrient, plus you’ll find RDA charts for everyone, informative visuals, fun facts, serving sizes and the 58 foods that are Nutrient Super Stars!

Buy now for instant digital access.

Calcium in Health and Disease

Getting enough calcium is vital for protecting against osteoporosis and bone fractures, especially in conjunction with vitamin D and magnesium. But, it can also help reduce your risk of kidney stones, protect against pregnancy-related high blood pressure, lower your risk of colorectal cancer (and improve survival following diagnosis), help you maintain a healthy body weight, and even reduce PMS symptoms!

Calcium and Bone Health

Scientists have studied the effects of calcium from food and supplements on a number of diseases—one of the most well-researched being osteoporosis. Across a variety of studies, including randomized controlled trials, increasing dietary calcium intake appears to modestly improve bone density in older adults, and calcium supplementation (especially combined with other bone-building nutrients) is associated with a significant reduction in fracture risk over time.

For example, a 2021 meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials found that supplementing with a combination of calcium and vitamin K led to significant increases in lumbar spine bone mineral density, especially with calcium intakes greater than 1000 mg daily. And a 2016 meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials, encompassing nearly 31,000 participants, found that calcium combined with vitamin D supplementation reduced total fracture risk by 15%. Risk of hip fractures, specifically, was reduced by 30%!

A 2005 review found that the bone-building benefits of increased exercise only happened when calcium intake was adequate (1000 mg or more), suggesting this nutrient is also important for supporting the anti-osteoporosis effects of other interventions.

However, it’s worth noting that the effects of calcium alone (versus calcium in combination with other interventions) are less clear-cut when it comes to bone health. Some early trials suggested that calcium could help slow bone post-menopausal bone loss and potentially protect against fractures, but more recent, higher-quality studies and meta-analyses have generally failed to find a significant effect. Overall, it appears the synergy between calcium and other micronutrients (or lifestyle factors like exercise) is important here!

Calcium and Kidney Stones

Calcium also may affect the risk of kidney stones—hard deposits that form from minerals and salts (usually calcium and oxalate) in the urine. Although high urinary calcium is a risk factor for kidney stones, dietary calcium actually appears protective of kidney stone formation, with a number of prospective cohort studies showing a significantly lower risk for individuals with the highest (versus lowest) dietary calcium intake. A 2013 analysis of Health Professionals Follow-up Study and Nurses’ Health Study I and II data, encompassing over 220,000 participants, found that those in the highest versus lowest quintile of non-dairy calcium intake had a 18 – % lower risk of kidney stones; for the highest quintile of dairy-derived calcium, the risk was 17 – 24% lower.

And, a 2002 intervention study involving a low-calcium diet (400 mg per day) for the treatment of high urinary calcium led to over a 50% increased risk of kidney stone recurrence compared to a normal-calcium diet (1200 mg per day)!

These effects may be due to calcium binding with oxalate in the intestine to form insoluble calcium oxalate salts, in turn reducing oxalate absorption and helping prevent high urinary oxalate levels (which is another risk factor for kidney stones). In fact, a small 2012 intervention study found that as long as calcium intake is adequate (1000 mg per day), even relatively large intakes of oxalate don’t affect kidney stone risk. This echoed the findings of an earlier intervention trial from 1998, which found that higher calcium intake protected against stone formation even when oxalate intake was 20-fold greater than levels normally consumed.

That being said, a small number of trials have suggested that calcium supplementation—opposed to dietary calcium—does increase kidney stone risk, especially when it’s taken with vitamin D. But, this finding hasn’t been consistent across studies, so we need more research to know for sure!

Calcium and Pregnancy

Calcium may also help protect against some pregnancy complications. A 2014 Cochrane Database Systematic Review, assessing 14 randomized controlled trials of expecting mothers, found that greater calcium intake protected against high blood pressure, preeclampsia, and preterm birth. Specifically, supplementation with at least 1 g of calcium daily was associated with a 35% lower risk of high blood pressure, a 55% lower risk of preeclampsia, and a 24% lower risk of preterm birth. For preeclampsia, the risk reduction was even greater for women with low baseline calcium intake (64% lower risk!), as well as for women initially at high risk of preeclampsia (78% lower risk!). This review even found that low-dose calcium supplementation could be helpful: doses under 1 g daily reduced preeclampsia risk by 62%, while also reducing incidence of low birthweight and neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Calcium and High Blood Pressure

Calcium also appears to have a modestly protective effect for hypertension, likely due to its role in the contraction and relaxing of blood vessels. A 2022 Cochrane Database Systematic Review, including a total of 20 randomized trials, found that increased calcium intake had a blood pressure reducing effect in normotensive participants, particularly those of younger age. A 2019 dose-response meta-analysis, including eight prospective cohort studies, likewise found a significant inverse association between calcium intake and hypertension risk, with the highest versus lowest category of calcium intake associated with an 11% risk reduction. In the dose-response analysis, every 500 mg daily increase in calcium intake was associated with a 7% lower risk! These findings persisted even after adjusting for body fat levels and intake of other blood-pressure-related minerals.

Calcium and Colorectal Cancer

In prospective cohort studies, higher calcium intakes (especially from dairy foods) have been linked to lower risk of colorectal cancer, and randomized controlled trials have found that consuming 1200 mg of elemental calcium daily for four years reduces colorectal cancer incidence by 26%. (However, trials using people that already had fairly high calcium intakes when the study began didn’t show any anti-cancer benefits of additional calcium supplementation—suggesting that baseline intake is an important factor here!) And, dose-response analyses have found that for every 300 mg increase in daily calcium intake, the odds of getting colorectal cancer drop by 5%, while odds of high-risk adenoma drop by 11%. There’s even evidence that higher calcium intake after colorectal cancer diagnosis is associated with a lower risk of death.

These protective effects are probably due to calcium’s ability to bind to harmful substances in the colon and prevent cancer cells from growing.

Calcium and Cervical Cancer

Some evidence suggests calcium could also play a protective role in cervical cancer. A 2021 cross-sectional study of over 2,300 Chinese women found that after adjusting for potential confounders, low dietary calcium intake was associated with a 52% greater risk of cervical cancer. A 2010 case-control study of Japanese women similarly found that higher calcium intake was protective against this type of cancer, with participants in the upper two quartiles of calcium intake having a 32 – 50% lower risk!

Calcium and Kidney Cancer

Although the research so far is limited, calcium may have associations with kidney cancer risk. A 2003 study of Canadian adults found among women, use of calcium supplements was associated with a significantly lower risk of developing renal cell carcinoma (kidney cancer). More research here is needed!

Calcium and Obesity

Some evidence indicates that high calcium intake (especially from dairy) is associated with lower body weight and abdominal obesity, and some clinical trials have demonstrated that consuming 1200 mg per day of dietary calcium can aid in weight loss more effectively than lower-calcium diets. This suggests that calcium plays a role in weight regulation, possibly by reducing lipogenesis (fat accumulation in fat cells), stimulating lipolysis (the breakdown of lipids) driving fat oxidation, improving hormone signaling, increasing muscle efficiency, regulating appetite, or reducing dietary fat absorption in the intestine (calcium can trap dietary fat into calcium soaps, which are insoluble and hence excreted instead of absorbed by the body).

A 2016 meta-analysis of 33 studies, including a total of 4733 participants, found that calcium supplementation was associated with body weight reductions among children, adolescents, men, premenopausal women, and women over the age of 60. However, these findings were limited to participants with normal BMI, with less benefit seen for overweight or obese individuals.

However, other research suggests calcium could be beneficial for people carrying extra weight as well. A 2004 clinical trial of 32 obese adults tested three energy-restricted diets, all with a 500-calorie energy deficit but varying levels and sources of calcium: a control diet with 400 to 500 mg of dietary calcium, a diet supplemented with 800 mg of calcium daily, and a diet high in dairy products (with a total of 1200 to 1300 mg of dietary calcium daily). Compared to the control diet, both the calcium-supplemented and high-dairy diets produced greater body fat loss. The calcium-supplemented diet enhanced fat loss by 38%, while the high-dairy diet enhanced fat loss by 64%! Abdominal fat loss was likewise augmented by increased calcium intake: for the control diet, only 19% of total fat loss came from this region, compared to 50% of total fat loss for the calcium-supplemented diet and 66% for the high-dairy diet.

It’s worth noting that when it comes dairy intake, findings related to body fat could be confounded by non-calcium components that promote weight loss through other mechanisms (like conjugated linoleic acid and branched chain amino acids).

Calcium and PMS

Interestingly, calcium may play a role in premenstrual syndrome (PMS). A 2020 systematic review of 14 studies (eight interventions and six observational studies) found that calcium supplementation significantly improved the incidence of PMS, as well as the number and severity of both physical and psychological symptoms—such as anxiety, depression, water retention, emotional changes, tiredness, and appetite. These findings were evident at calcium doses ranging from 500 to 1200 mg daily, taken for periods of two to three months.

These beneficial effects may be due to improved nervous system function (better mood) and adequate muscular signaling (reduced cramping) resulting from increased calcium intake!

Calcium and Diabetic Retinopathy

Some evidence suggests calcium could play a protective role in diabetic retinopathy—a diabetes complication affecting blood vessels in the retina. A 2022 cross-sectional retrospective study of National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey data found that higher dietary calcium intake was associated with lower incidence of this condition. Participants consuming at least 550 mg daily had a 32% lower incidence! More studies are needed to confirm this finding and explore causality.

Calcium and Sarcopenia

Calcium is one of the minerals identified as helping protect against sarcopenia, or age-related loss of muscle and strength. A 2018 systematic review, encompassing 10 studies of older adults, found that calcium intake was significantly associated with muscle mass. A 2013 analysis of data from the fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey likewise found that for adults over the age of 60, daily calcium intake was positively associated with skeletal mass. After adjusting for potential confounders, participants in the highest (versus lowest) tertile of calcium intake had 70% lower risk of sarcopenia!

Didn’t know calcium was this amazing? Maybe your friends will enjoy this too!

Health Effects of Calcium Deficiency

Data suggests that upwards of 40% of adults aren’t getting enough calcium in their diet. This can be particularly true for people with lactose intolerance, or other individuals who avoid dairy products without replacing them with other calcium-rich foods. But, the symptoms of dietary deficiency or insufficiency aren’t outwardly obvious at first, and won’t show up on blood tests as low serum values (as happens with some nutrient deficiencies) due to our body’s ability to keep blood calcium levels stable regardless of dietary intake.

Because our bodies tightly regulate the amount of calcium in our blood by borrowing it from bone tissue as needed, insufficient calcium intake can lead to excessive bone resorption—ultimately leading to osteopenia, osteoporosis, and increased risk of fracture, as well as increased risk of dental decay. And in children and adolescents, inadequate calcium during growing years can prevent them from reaching optimal peak bone mass. In extreme cases, ongoing calcium deficiency (especially if combined with other conditions affecting calcium absorption or metabolism, like hypoparathyroidism) can lead to symptoms like confusion, muscle cramps and spasms, memory loss, brittle nails, hallucinations, numbness, and tingling hands or feet.

When calcium levels do get too low in the blood, it’s usually a consequence of abnormal parathyroid function, vitamin D deficiency, kidney failure, or alcoholism-induced magnesium deficiency, which can all happen regardless of actual calcium intake. Testing whether there has been adequate intake of calcium over time is best done with a bone scan, because this is a reliable measure of where calcium is stored.

Merch and Household Goods

Check out our collection of practical and nerdtastic T-shirts, totes, and more!

Problems From Too Much Calcium

Excess calcium carries some unique risks, such as hypercalcemia (abnormally high calcium levels in the blood). Although this condition is typically due to overactive parathyroid glands or certain cancers, it can sometimes be caused by taking high-dose calcium supplements with absorbable alkali (such as over-the-counter calcium carbonate products, like Tums or Rolaids). This risk is particularly high among postmenopausal women, and is seen when taking calcium supplements ranging from 1.5 to 16.5 grams per day for at least two years. When hypercalcemia occurs, it triggers a shift in the body’s acid-base balance towards the alkaline state, eventually damaging kidney function and becoming fatal if left untreated.

Some evidence has also linked calcium supplements to an increased risk of heart attacks. This may be due to excess calcium from dietary supplements becoming incorporated into arterial plaque, instead of depositing into skeletal tissue or being excreted. However, the evidence isn’t totally consistent here, and dietary calcium (versus calcium in supplement form) is generally associated with less calcification in the arteries and better overall cardiovascular health. So, while food sources of calcium are unlikely to negatively impact heart health, it may be worth seeking medical advice from your health care provider before beginning calcium supplementation—especially if you have a family history of heart disease or other cardiovascular risk factors.

Some forms of calcium supplements (such as calcium carbonate and calcium lactate) can cause side effects like constipation, bloating, and abdominal pain. In these cases, calcium citrate can be an effective alternative, since it produces fewer gastrointestinal effects. What’s more, calcium carbonate can be poorly absorbed among people taking acid-reducing medications, since this form of calcium requires stomach acid for absorption; other forms of calcium may be more effective under these circumstances.

Additionally, in observational and intervention studies, high calcium intakes from dairy have occasionally been linked with a greater incidence of prostate cancer, and a few studies have found that calcium supplementation is associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease. More research is needed to fully understand these links, whether they’re specific to calcium or to certain components of dairy (such as insulin-like growth factor-I), and who might be most at risk. In general, calcium appears to be safe for these conditions as long as total intake doesn’t exceed the recommended upper limit of 2000 to 2500 mg per day.

How Much Calcium Do We Need?

As with most nutrients, the body needs varying amounts of calcium as we age or go through different health experiences, with the highest requirement being during adolescence and pregnancy (1300 mg per day). The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for adults 19 to 50 years old is 1000 mg per day, after which the recommended amount increases to 1200 mg per day—especially after menopause. When estimating intake, though, it’s important to keep in mind that calcium bioavailability varies among different foods, and can also be inhibited by some drugs that reduce calcium absorption!

| 0 – 6 months | |||||

| 6 months to < 12 months | |||||

| 1 yr – 3 yrs | |||||

| 4 yrs – 8 yrs | |||||

| 9 yrs – 13 yrs | |||||

| 14 yrs – 18 yrs | |||||

| 19 yrs – 50 yrs | |||||

| 51+ yrs | 1200 (71+ yrs) | ||||

| Pregnant (14 – 18 yrs) | |||||

| Pregnant (19 – 30 yrs) | |||||

| Pregnant (31 – 50 yrs) | |||||

| Lactating (14 – 18 yrs) | |||||

| Lactating (19 – 30 yrs) | |||||

| Lactating (31 – 50 yrs) |

Nutrient Daily Values

Nutrition requirements and recommended nutrient intake for infants, children, adolescents, adults, mature adults, and pregnant and lactating individuals.

Want to know the top 500 most nutrient-dense foods?

Top 500 Nutrivore Foods

The Top 500 Nutrivore Foods e-book is an amazing reference deck of the top 500 most nutrient-dense foods according to their Nutrivore Score. Think of it as the go-to resource for a super-nerd, to learn more and better understand which foods stand out, and why!

If you are looking for a quick-reference guide to help enhance your diet with nutrients, and dive into the details of your favorite foods, this book is your one-stop-shop!

Buy now for instant digital access.

Good Food Sources of Calcium

The following foods are also excellent or good sources of calcium, containing at least 10% (and up to 50%) of the daily value per serving.

Everything You Need to Jump into Nutrivore TODAY!

Nutrivore Quickstart Guide

The Nutrivore Quickstart Guide e-book explains why and how to eat a Nutrivore diet, introduces the Nutrivore Score, gives a comprehensive tour of the full range of essential and important nutrients!

Plus, you’ll find the Top 100 Nutrivore Score Foods, analysis of food groups, practical tips to increase the nutrient density of your diet, and look-up tables for the Nutrivore Score of over 700 foods.

Buy now for instant digital access.

Citations

Expand to see all scientific references for this article.

Allender PS, Cutler JA, Follmann D, Cappuccio FP, Pryer J, Elliott P. Dietary calcium and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 1996 May 1;124(9):825-31. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-9-199605010-00007.

Alvir JM, Thys-Jacobs S. Premenstrual and menstrual symptom clusters and response to calcium treatment. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1991;27(2):145-8.

Arab A, Rafie N, Askari G, Taghiabadi M. Beneficial Role of Calcium in Premenstrual Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Current Literature. Int J Prev Med. 2020 Sep 22;11:156. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_243_19.

Bonovas S, Fiorino G, Lytras T, Malesci A, Danese S. Calcium supplementation for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 May 14;22(18):4594-603. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i18.4594.

Borer KT. Physical activity in the prevention and amelioration of osteoporosis in women: interaction of mechanical, hormonal and dietary factors. Sports Med. 2005;35(9):779-830. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200535090-00004.

Borghi L, Schianchi T, Meschi T, Guerra A, Allegri F, Maggiore U, Novarini A. Comparison of two diets for the prevention of recurrent stones in idiopathic hypercalciuria. N Engl J Med. 2002 Jan 10;346(2):77-84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010369.

Calcium: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Dietary Supplements. 2022 Jun 2.

Chen YY, Chen YJ. Association between Dietary Calcium and Potassium and Diabetic Retinopathy: A Cross-Sectional Retrospective Study. Nutrients. 2022 Mar 4;14(5):1086. doi: 10.3390/nu14051086.

Chung M, Tang AM, Fu Z, Wang DD, Newberry SJ. Calcium Intake and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Dec 20;165(12):856-866. doi: 10.7326/M16-1165. Epub 2016 Oct 25.

Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell. 2007 Dec 14;131(6):1047-58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028.

Cormick G, Ciapponi A, Cafferata ML, Cormick MS, Belizán JM. Calcium supplementation for prevention of primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Jan 11;1(1):CD010037. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010037.pub4.

Hess B, Jost C, Zipperle L, Takkinen R, Jaeger P. High-calcium intake abolishes hyperoxaluria and reduces urinary crystallization during a 20-fold normal oxalate load in humans. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998 Sep;13(9):2241-7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.9.2241.

Hofmeyr GJ, Lawrie TA, Atallah AN, Duley L, Torloni MR. Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jun 24;(6):CD001059. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001059.pub4.

Hosono S, Matsuo K, Kajiyama H, Hirose K, Suzuki T, Kawase T, Kidokoro K, Nakanishi T, Hamajima N, Kikkawa F, Tajima K, Tanaka H. Association between dietary calcium and vitamin D intake and cervical carcinogenesis among Japanese women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010 Apr;64(4):400-9. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.28.

Hu J, Mao Y, White K; Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research Group. Diet and vitamin or mineral supplements and risk of renal cell carcinoma in Canada. Cancer Causes Control. 2003 Oct;14(8):705-14. doi: 10.1023/a:1026310323882.

Hu L, Ji J, Li D, Meng J, Yu B. The combined effect of vitamin K and calcium on bone mineral density in humans: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021 Oct 14;16(1):592. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02728-4.

Ito T, Jensen RT. Association of long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy with bone fractures and effects on absorption of calcium, vitamin B12, iron, and magnesium. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010 Dec;12(6):448-57. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0141-0.

Jayedi A, Zargar MS. Dietary calcium intake and hypertension risk: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019 Jul;73(7):969-978. doi: 10.1038/s41430-018-0275-y.

Lange JN, Wood KD, Mufarrij PW, Callahan MF, Easter L, Knight J, Holmes RP, Assimos DG. The impact of dietary calcium and oxalate ratios on stone risk. Urology. 2012 Jun;79(6):1226-9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.01.053.

Li P, Fan C, Lu Y, Qi K. Effects of calcium supplementation on body weight: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016 Nov;104(5):1263-1273. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.136242.

Murphy N, Norat T, Ferrari P, Jenab M, Bueno-de-Mesquita B, Skeie G, Olsen A, Tjønneland A, Dahm CC, Overvad K, Boutron-Ruault MC, Clavel-Chapelon F, Nailler L, Kaaks R, Teucher B, Boeing H, Bergmann MM, Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Palli D, Pala V, Tumino R, Vineis P, Panico S, Peeters PH, Dik VK, Weiderpass E, Lund E, Garcia JR, Zamora-Ros R, Pérez MJ, Dorronsoro M, Navarro C, Ardanaz E, Manjer J, Almquist M, Johansson I, Palmqvist R, Khaw KT, Wareham N, Key TJ, Crowe FL, Fedirko V, Gunter MJ, Riboli E. Consumption of dairy products and colorectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). PLoS One. 2013 Sep 2;8(9):e72715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072715.

Myung SK, Kim HB, Lee YJ, Choi YJ, Oh SW. Calcium Supplements and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2021 Jan 26;13(2):368. doi: 10.3390/nu13020368.

Seo MH, Kim MK, Park SE, Rhee EJ, Park CY, Lee WY, Baek KH, Song KH, Kang MI, Oh KW. The association between daily calcium intake and sarcopenia in older, non-obese Korean adults: the fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES IV) 2009. Endocr J. 2013;60(5):679-86. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.ej12-0395.

Shobeiri F, Araste FE, Ebrahimi R, Jenabi E, Nazari M. Effect of calcium on premenstrual syndrome: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2017 Jan;60(1):100-105. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2017.60.1.100.

Silk LN, Greene DA, Baker MK. The Effect of Calcium or Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation on Bone Mineral Density in Healthy Males: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2015 Oct;25(5):510-24. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2014-0202.

Soares MJ, Pathak K, Calton EK. Calcium and vitamin D in the regulation of energy balance: where do we stand? Int J Mol Sci. 2014 Mar 20;15(3):4938-45. doi: 10.3390/ijms15034938.

Taylor EN, Curhan GC. Dietary calcium from dairy and nondairy sources, and risk of symptomatic kidney stones. J Urol. 2013 Oct;190(4):1255-9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.03.074.

van Dronkelaar C, van Velzen A, Abdelrazek M, van der Steen A, Weijs PJM, Tieland M. Minerals and Sarcopenia; The Role of Calcium, Iron, Magnesium, Phosphorus, Potassium, Selenium, Sodium, and Zinc on Muscle Mass, Muscle Strength, and Physical Performance in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018 Jan;19(1):6-11.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.05.026.

Wang Z, Wang W, Yang A, Zhao W, Yang J, Wang Z, Wang W, Su X, Wang J, Song J, Li L, Lv W, Li D, Liu H, Wang C, Hao M. Lower dietary mineral intake is significantly associated with cervical cancer risk in a population-based cross-sectional study. J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;12(1):111-123. doi: 10.7150/jca.39806.

Weaver CM, Alexander DD, Boushey CJ, Dawson-Hughes B, Lappe JM, LeBoff MS, Liu S, Looker AC, Wallace TC, Wang DD. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and risk of fractures: an updated meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporos Int. 2016 Jan;27(1):367-76. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3386-5.

Wood RJ, Zheng JJ. High dietary calcium intakes reduce zinc absorption and balance in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997 Jun;65(6):1803-9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.6.1803.

Yang W, Ma Y, Smith-Warner S, Song M, Wu K, Wang M, Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS, Poylin V, Ng K, Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Zhang X. Calcium Intake and Survival after Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2019 Mar 15;25(6):1980-1988. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2965.

Zemel MB, Shi H, Greer B, Dirienzo D, Zemel PC. Regulation of adiposity by dietary calcium. FASEB J. 2000 Jun;14(9):1132-8.

Zemel MB, Thompson W, Milstead A, Morris K, Campbell P. Calcium and dairy acceleration of weight and fat loss during energy restriction in obese adults. Obes Res. 2004 Apr;12(4):582-90. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.67.

Ready to Make Healthy Eating Feel Effortless?

Join the FREE 90-day Nutrivore90 Challenge and build lasting habits with no food rules, no guilt—just real progress.

- Weekly downloads, journal prompts, and reflection tools—all completely free.

- Focus on nutrient density, not restriction

- Starts September 1st!