Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis, characterized by the gradual breakdown of cartilage—the smooth, protective tissue covering the ends of bones in a joint. This degeneration leads to pain, stiffness, swelling, and reduced joint mobility. As the cartilage wears away, bones may rub against each other, causing further damage and the formation of bony growths called bone spurs. Over time, osteoarthritis can significantly impact daily activities, including walking, climbing stairs, and even gripping objects.

While osteoarthritis can affect any joint, it most commonly occurs in weight-bearing joints such as the knees, hips, and spine, as well as in the hands. Although it is often considered a disease of aging, osteoarthritis can develop at any age due to injury or genetic factors. Managing osteoarthritis effectively involves understanding its causes, risk factors, and prevention strategies.

Osteoarthritis is a leading cause of disability in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 32.5 million adults have osteoarthritis. It is most prevalent in individuals over the age of 50, and the likelihood of developing osteoarthritis increases with age. Women are disproportionately affected, particularly after menopause, potentially due to hormonal changes that influence joint health.

The economic burden of osteoarthritis is significant, with billions of dollars spent annually on medical care, lost productivity, and disability-related costs. The condition also has a profound impact on quality of life, limiting physical activity and contributing to mental health challenges such as depression and anxiety.

What Are Causes and Risk Factors for Osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis develops when the balance between cartilage breakdown and repair is disrupted, leading to a gradual loss of cartilage and joint damage. The exact causes of osteoarthritis are complex and multifactorial, involving a combination of mechanical, genetic, and environmental factors.

- Cartilage Wear and Tear: Over time, repetitive use of joints can lead to micro-damage in the cartilage. When the body’s repair mechanisms cannot keep up with the rate of damage, cartilage gradually deteriorates. Certain occupations or sports that involve repetitive stress on joints can increase the risk of osteoarthritis.

- Joint Injuries: Acute injuries, such as ligament tears, fractures, or meniscal damage, can alter the joint’s structure and mechanics, increasing the risk of osteoarthritis later in life. Preventing or managing joint injuries can reduce the likelihood of developing osteoarthritis later in life.

- Genetic Factors: A family history of osteoarthritis may predispose individuals to the condition, suggesting a genetic component in cartilage structure and repair, especially in cases of hand or knee-specific disease.

- Chronic Inflammation: Low-grade inflammation within the joint can contribute to cartilage breakdown and joint damage over time.

- Obesity: Excess body weight places additional stress on weight-bearing joints, accelerating cartilage wear. Fat tissue also releases inflammatory chemicals that may contribute to joint damage.

- Biomechanical Stress: Poor joint alignment, repetitive movements, and occupational activities that involve heavy lifting or kneeling can increase mechanical stress on joints, leading to osteoarthritis.

- Age: The risk of osteoarthritis increases significantly with age, as cartilage naturally thins and becomes less resilient over time.

- Gender: Women are more likely than men to develop osteoarthritis, particularly in the knees and hands, potentially due to hormonal influences.

- Muscle Weakness: Weak muscles around a joint can lead to improper joint alignment and increased stress on cartilage.

How Do You Reduce Risk of Osteoarthritis?

While some risk factors for osteoarthritis, such as age and genetics, cannot be changed, many are modifiable through lifestyle adjustments. Preventive strategies focus on protecting joint health, reducing mechanical stress, and maintaining overall physical well-being.

- Maintain a Healthy Weight: Losing excess weight reduces the strain on weight-bearing joints, lowering the risk of osteoarthritis and slowing disease progression in those already affected. A weight loss of even 5-10% can have significant benefits for joint health.

- Engage in Regular Exercise: Low-impact activities like walking, swimming, and cycling help strengthen muscles around the joints, improve joint stability, and enhance flexibility without placing excessive stress on the joints. Strength training helps support joint alignment and reduces the risk of cartilage damage.

- Protect Joints During Activities: Using proper techniques during physical activities or sports can minimize joint injuries. For example, wearing protective gear or ensuring proper footwear can reduce joint stress. Avoid repetitive motions or positions that strain the joints, such as prolonged kneeling or squatting.

- Adopt a Joint-Healthy Diet: A diet rich in anti-inflammatory foods, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fatty fish, and nuts, may help reduce joint inflammation and support overall health. Foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids, like salmon and walnuts, are particularly beneficial for joint health. Adopting a Nutrivore diet will help to ensure all your nutrient needs are met.

- Prevent and Manage Joint Injuries: Prompt treatment of joint injuries and physical therapy can help maintain proper joint function and prevent osteoarthritis. Avoid overuse of joints during recovery periods to prevent further damage.

- Stay Active but Avoid Overuse: Strike a balance between staying active and avoiding overuse of joints. Gradual increases in activity levels can help protect joints from unnecessary strain.

- Consider Physical Therapy: For individuals with joint weakness or misalignment, physical therapy can improve joint mechanics, relieve pain, and prevent further cartilage damage.

How Do Nutrients Improve Osteoarthritis?

A Nutrivore approach emphasizes nutrients that help the body function at its best—including joint tissues. Current research highlights the following nutrients for osteoarthritis support, along with food sources to help you incorporate these nutrients through your diet.

| Nutrient | How it Supports Osteoarthritis | Top Food Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K | Vitamin K may protect joint structures by supporting vitamin-K-dependent cartilage and bone proteins. Higher intake has been associated with reduced cartilage damage, improved symptoms, and lower risk of osteoarthritis incidence and progression, while vitamin K antagonist use increases OA risk. | Top food sources include leafy green vegetables such as kale, chard, collards, spinach, broccoli, and Brussels sprouts for vitamin K1, and natto, organ meats, egg yolks, certain hard cheeses, butter, pork, and dark chicken meat for vitamin K2. |

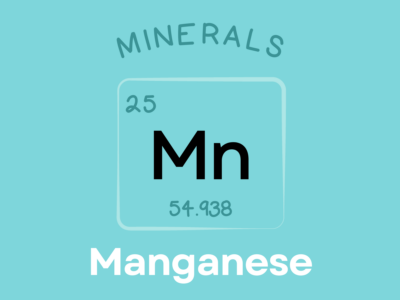

| Manganese | Some trials show that manganese, when combined with glucosamine and chondroitin, improves osteoarthritis symptoms, although independent effects of manganese remain unclear. More research is needed to determine manganese’s direct role in protecting cartilage. | Top food sources include fish and shellfish such as mussels, clams, and oysters, along with nuts, seeds, sweet potatoes, legumes, leafy greens, tea, cruciferous vegetables, and whole grains like oatmeal, brown rice, and bran cereals. |

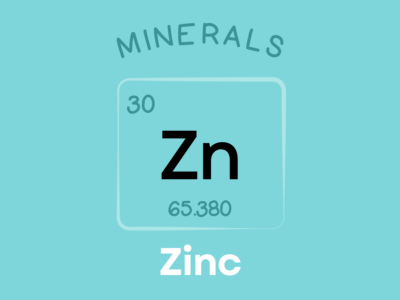

| Zinc | Zinc may help protect cartilage by regulating oxidative stress and inflammatory processes, with some human studies showing slower progression of subchondral sclerosis in higher-intake groups, though other findings suggest risk may increase with excessive intake. More research is needed to clarify the relationship. | Good sources of zinc include red meat, some organ meats (especially liver and heart), seafood (especially oysters), eggs, legumes, nuts, and whole grains. |

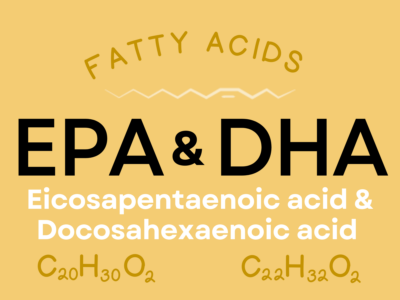

| EPA & DHA | EPA and DHA demonstrate anti-inflammatory effects that may improve pain and joint function in osteoarthritis. Meta-analyses show that supplementation can significantly reduce symptoms, and low doses can be as effective as higher doses for knee OA. | Top food sources include fatty cold-water fish like salmon, herring, mackerel, sardines, and menhaden, algae, cod liver oil, and shellfish such as mussels, crab, oysters, and squid. |

Nutrients for Osteoarthritis

Nutrients for Osteoarthritis explains all the nutrients that matter most for joint health, mobility, and osteoarthritis risk! This e-book is exclusively available in Patreon!

Plus every month, you’ll gain exclusive and early access to a variety of resources, including a weekly video podcast, a new e-book in a series, nutrient fun factsheet, and more! Sign up now and also get 5 free Nutrivore guides as a welcome gift! Win-win-win!

Benefits of a Food-Based Approach

A nutrient-focused, whole-food approach can play a supportive role in managing many health conditions, especially when paired with healthy lifestyle habits like physical activity and good-quality sleep. A food-based approach to nutrition offers health benefits that go far beyond what supplements can provide. Whole foods deliver a natural balance of nutrients that work synergistically, meaning vitamins, minerals, phytonutrients, healthy fats, carbohydrates and fiber can support each other for better overall health outcomes. Nutrient-dense foods like leafy greens, fruits, legumes, nuts, seeds, and fish are efficient, cost-effective, and widely accessible options that fit easily into a healthy diet and good eating patterns. By choosing whole foods first, you not only support a more balanced diet but also avoid the added costs and potential nutrient insufficiencies that can come with eating highly processed foods and relying solely on supplements to make up the shortfall.

The variety of nutrient-dense foods available across food groups makes it easy to enjoy a satisfying, diverse, and plant-forward (though not solely plant-based) way of eating. Many of these foods provide additional health benefits including antioxidants (which are anti-inflammatory), insoluble fiber for gut health, which in turn supports overall health and wellness. Because whole foods are often more accessible and affordable than supplements, a food-based approach creates a sustainable foundation for long-term well-being.

Nutrivore encourages filling your plate with a wide range of nutrient-rich foods without the need for restrictive rules, making it easy to prevent and support health conditions through the simple power of food. With a Nutrivore approach (maximizing nutrient density across food groups), a nutritious, balanced, and enjoyable way of eating becomes both achievable and flexible for any lifestyle. While it isn’t a replacement for medical care or the advice of a registered dietitian, a balanced, food-first approach can complement your overall strategy for improving many health conditions and support long-term health goals.