Key Takeaways (expand)

- 58% of the calories consumed in the USA come from ultra-processed and hyperpalatable foods, which are displacing more nutritionally valuable options in the average American diet.

- Because dietary guidelines have historically focused on nutritionally underwhelming foods, very few Americans are meeting current serving targets for nutrient-dense foods like vegetables.

- Weight-loss and fad diets have propelled diet myths, healthism, and restrictive eating patterns that magnify dietary nutrient shortfalls when people unnecessarily avoid nutrient-dense, healthful foods.

Many of us think that nutrient deficiencies are mainly a problem in developing nations (whereas in Westernized countries like the United States, our problem is that we have too much food!), but this is a misconception. Nearly everyone has dietary shortfalls in essential nutrients.

The Prevalence of Nutrient Deficiencies and Insufficiencies

Almost everyone has dietary shortfalls of essential nutrients, which increases risk for chronic disease, including type 2 diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, asthma, chronic kidney disease, neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease, and infection.

In addition, about one third of Americans are at risk of nutrient deficiency, resulting in diseases of malnutrition like anemia, scurvy, rickets and night blindness.

The high prevalence of nutrient insufficiencies and deficiencies are the direct result of low dietary intake, and are contributing to diseases of malnutrition and chronic illness. Why do our diets fall so short of the mark when it comes to our body’s nutritional requirements? There are three main contributors:

- ultra-processed and hyperpalatable foods displacing more nutritionally valuable options

- dietary guidelines historically focusing on nutritionally underwhelming foods

- weight-loss and fad diets propelling diet myths, healthism, and restrictive eating patterns

Cause #1: Ultra-Processed and Hyperpalatable Foods

The Standard American Diet is energy-rich and nutrient-poor: the types of food that many people eat each day are high in added sugars, fats and refined carbohydrates, but devoid of the vitamins and minerals (and other health-promoting compounds) found in whole and minimally-processed foods.

Generally, the more a food is manipulated to make it shelf-stable, convenient, cheap, and addictively delicious, the fewer valuable nutrients remain in that food.

Studies have shown that nearly 58% of the calories consumed in the USA are derived from ultra-processed foods. Ultra-processed foods are made mostly from ingredients extracted from foods, such as vegetable oils, corn starch, high-fructose corn syrup, and table sugar, which contain only negligible amounts of nutrients. Furthermore, it’s common for ultra-processed foods to have many added ingredients, including salt, sugar, fat, flavorings, emulsifiers, food dyes, flavor enhancers (like monosodium glutamate) or preservatives, making them hyperpalatable, i.e., so addictively delicious that eating that food overrides the body’s natural satiety signals and triggers overeating.

Examples of these ultra-processed, hyperpalatable foods are soft drinks, fast food, pizza, packaged cookies, cakes and salty snacks. Generally, the more a food is manipulated to make it shelf-stable, convenient, cheap, and addictively delicious, the fewer valuable nutrients remain in that food.

| Food | Portion Size | Type of Food | Sugar | Fat | Sodium | # of Ingredients |

| Apple | 1 medium | Traditional | 19 g | 0 g | 2 mg | 1 |

| Chicken breast, roasted | 3 ounces | Traditional | 0 g | 3 g | 63 mg | 1 |

| Lettuce | 1 cup shredded | Traditional | 0 g | 0 g | 10 mg | 1 |

| Tomato | 1 medium | Traditional | 3 g | 0 g | 6 mg | 1 |

| Orange | 1 cup, sections | Traditional | 17 g | 0 g | 0 mg | 1 |

| Coca-cola | 1 can | Hyperpalatable | 39 g | 0 g | 45 mg | 6 |

| Dairy Queen Chocolate Ice Cream Cone | 1 medium cone | Hyperpalatable | 34 g | 10 g | 160 mg | 22 |

| McDonald’s French Fries | 1 medium | Hyperpalatable | 0 g | 19 g | 270 mg | 9 |

| Cinnamon Toast Crunch Cereal | ¾ cup (milk not included) | Hyperpalatable | 10 g | 3 g | 217 mg | 27 |

| DiGiorno Pepperoni Pizza | ⅙ of pizza | Hyperpalatable | 7 g | 13 g | 910 mg | 8 |

The more processed or refined a food or food ingredient is, the more nutrients are degraded and ultimately stripped out of it. For example, there is a difference as wide as the Grand Canyon between the superb micronutrient content of beets (which are especially rich in vitamin B9 and manganese but also contain vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, and C, as well as calcium, potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, zinc, copper, and selenium) and the micronutrient content of table sugar, which contains no vitamins or minerals whatsoever, even though many brands are made from sugar beets—in fact, 55% of US sugar production comes from sugar beets rather than sugar cane.

| Beets (100 g or ¾ cup) | Table Sugar (7 g or 2 tsp) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sugars | 7 g | 7 g |

| Vitamin A | 2 µg* | 0 µg |

| Vitamin B1 | 31 µg | 0 µg |

| Vitamin B2 | 40 µg | 1 µg |

| Vitamin B3 | 334 µg | 0 µg |

| Vitamin B5 | 200 µg | 0 µg |

| Vitamin B6 | 67 µg | 0 µg |

| Vitamin B9 | 109 µg | 0 µg |

| Vitamin C | 4.9 mg | 0 mg |

| Calcium | 16 mg | 0 mg |

| Potassium | 325 mg | 0 mg |

| Magnesium | 23 mg | 0 mg |

| Phosphorus | 40 mg | 0 mg |

| Zinc | 400 µg | 0 µg |

| Copper | 100 µg | 0 µg |

| Selenium | 0.7 µg | 0 µg |

| Manganese | 300 µg | 0 µg |

| Fiber | 2.8 g | 0g |

A food that delivers a ton of calories but not much in the way of nutrients is the antithesis of the Nutrivore philosophy. But, it is important to emphasize that Nutrivore principals apply to the whole diet and not individual foods, so there can still be room for a few empty calories in an otherwise nutrient-focused diet.

While some ultra-processed foods can absolutely fit into a Nutrivore template, it can be challenging to switch to a whole-foods focused diet while continuing to consume ultra-processed foods. The surge in dopamine caused by these foods causes an intense feeling of pleasure, which leads to developing a strong preference for these foods but also addiction-like deficits in brain reward function, meaning we need more and more of these hyperpalatable foods to get that good feeling from eating them. Nutrient-dense whole foods just can’t compete and will often taste bland or bitter to someone whose taste buds are attuned to ultra-processed foods.

While no food is off-limits on Nutrivore, it’s important to be aware of how ultra-processed foods are not only displacing more nutrient-dense options, but perhaps also making choosing a healthier option feel (and taste) much more difficult.

There’s another reason to consider avoiding them: Studies show that when people eat a diet plentiful in ultra-processed foods, they tend to eat more. One study fed participants a diet of 83% of calories from ultra-processed foods or 83% of calories from unprocessed foods for two weeks, with a cross-over design so each participant ate one diet for two weeks before switching to the other diet for an additional two weeks. The meals the participants were fed were matched for total calories, fat, carbohydrate, protein, fiber, sugars, and sodium and the participants were told to eat as much, or as little, as they liked. While on the ultra-processed food arm of the study, participants ate an average of 500 calories more per day and gained an average of two pounds, whereas they lost two pounds on average while on the unprocessed food arm of the study. Ultra-processed foods trigger overeating while delivering very little in the way of valuable nutrition.

While no food is off-limits on Nutrivore, it’s important to be aware of how ultra-processed foods are not only displacing more nutrient-dense options, but perhaps also making choosing a healthier option feel (and taste) much more difficult.

Everything You Need to Jump into Nutrivore TODAY!

Nutrivore Quickstart Guide

The Nutrivore Quickstart Guide e-book explains why and how to eat a Nutrivore diet, introduces the Nutrivore Score, gives a comprehensive tour of the full range of essential and important nutrients!

Plus, you’ll find the Top 100 Nutrivore Score Foods, analysis of food groups, practical tips to increase the nutrient density of your diet, and look-up tables for the Nutrivore Score of over 700 foods.

Buy now for instant digital access.

Cause #2: Dietary Guidelines

Yet, even eating what many people believe to be a healthy diet, however, can leave our bodies starved for micronutrients. And this falls on the shoulders of dietary guidelines.

The U. S. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee has been criticized by experts for being too influenced by the food industry, while failing to protect against bias and partiality in its review of the relevant science, and accepting weak evidentiary support as adequate justification to construct the USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans. As a result, there are many aspects of the dietary guidelines that are wrought with controversy, and the impact it two-fold:

- First, there is a large amount of cynicism and apathy towards USDA dietary guidelines, resulting in very few adherents.

- Second, even if you followed the USDA dietary guidelines perfectly, you’d still have nutrient shortfalls.

The types and quantities of food and drink that most Americans consume do not align with the USDA dietary recommendations. The Healthy Eating Index (HEI) is a measurement of how well someone’s diet follows the USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and analyses show that American adults average a measly score of 58 out of 100. Separate analyses from the USDA Economic Research Service reveal that only 9% of Americans try to adhere to the USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans; indeed only about one-third of Americans have even heard of MyPlate.

The promotion of grains (and not specific as to whether whole or refined) as the base of the Food Guide Pyramid from 1992 to 2011 continues to reverberate through American food choices, displacing more nutrient-dense options like vegetables and fruit (which were initially recommended to form the base of the Food Guide Pyramid, as Luise Light, the Director of Dietary Guidance and Nutrition Education Research at the time recounts in her book, What to Eat). There are certainly established benefits to moderate whole grain consumption, attributable mainly to their fiber content but also some benefits of phytate consumption. But, when too many grains, especially refined grains, displace nutrient-dense fruits and vegetables, nutrient sufficiency without energy excess becomes out of reach.

A 2019 analysis by the CDC revealed that only 10% of American adults eat the current recommended intake of vegetables (which is lower than what scientific studies show would be optimal for improving health outcomes, see Importance of Vegetables and Fruit), and only 12.5% of adults eat the current recommended intake of fruit (which is in the range of what is supported by scientific studies). In fact, the average vegetable consumption is a mere 1.64 cup equivalents of vegetables per day. In contrast, Americans consume about double the recommended amount of grains, averaging 6.7 ounce equivalents per day, and the consumption of grains has increased by 35% compared to 1970 (this increase is mainly driven by a 23% increased intake of wheat-based products and a 202% increased intake of corn-based products).

The fact that grains were touted for so long as being the foundation of a healthy diet may be the biggest contributor to the mismatch between the nutrition our bodies need and how much we actually get. The Food Guide Pyramid recommended 6 to 11 servings of grains daily (a serving being a 1-ounce equivalent, and the Food Guide Pyramid did not specify whole versus refined grains), but the current MyPlate recommendation is 3 servings of whole grains daily for women and 3.5 to 4 servings for men—most Americans are not aware that the serving target for grains has decreased.

Simply swapping the excess grain servings in the average American diet for vegetables would have a profound impact on the nutrient density of our diets. Let’s explore why this is in a bit more depth.

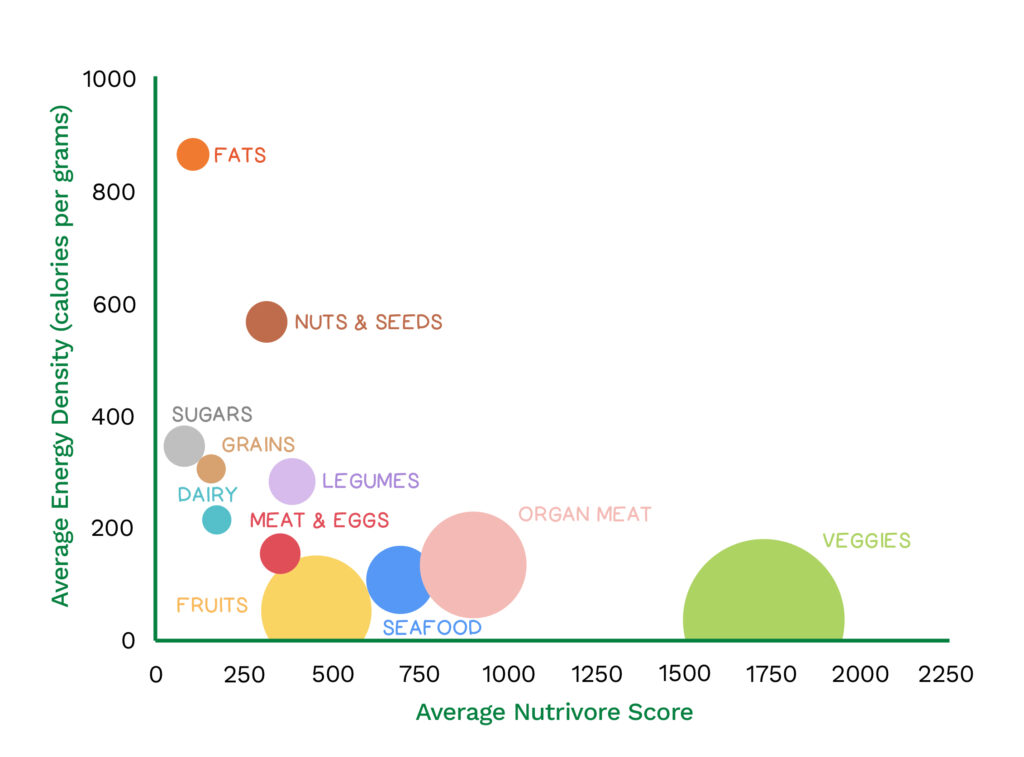

Nutrient density analysis shows that whole grains have less nutrients per 100 calories on average than meat, fish, shellfish, eggs, legumes, nuts, seeds, and fruits and way, way, way less nutrients per 100 calories than vegetables. In addition, grains are calorie-dense foods, containing a much higher number of calories per 100 grams than most other food, comparable to sugars. And of course, refined grains have very little to offer nutritionally, unless fortified.

Vegetables and fruits contain up to ten times more vitamins and minerals than grains, just as much fiber, and high amounts of health-promoting phytonutrients.

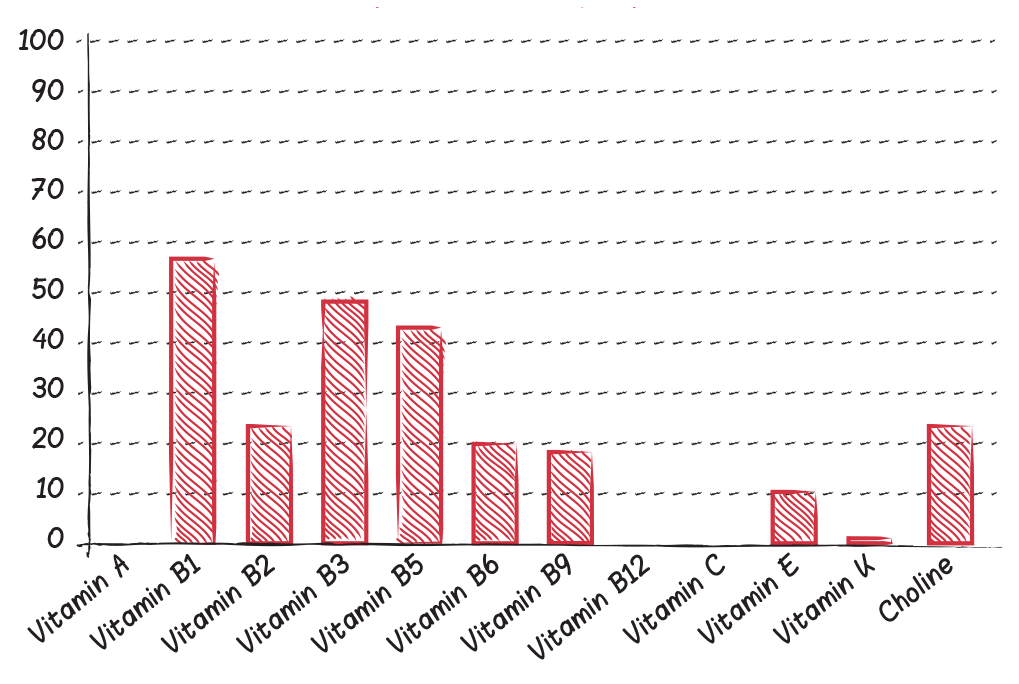

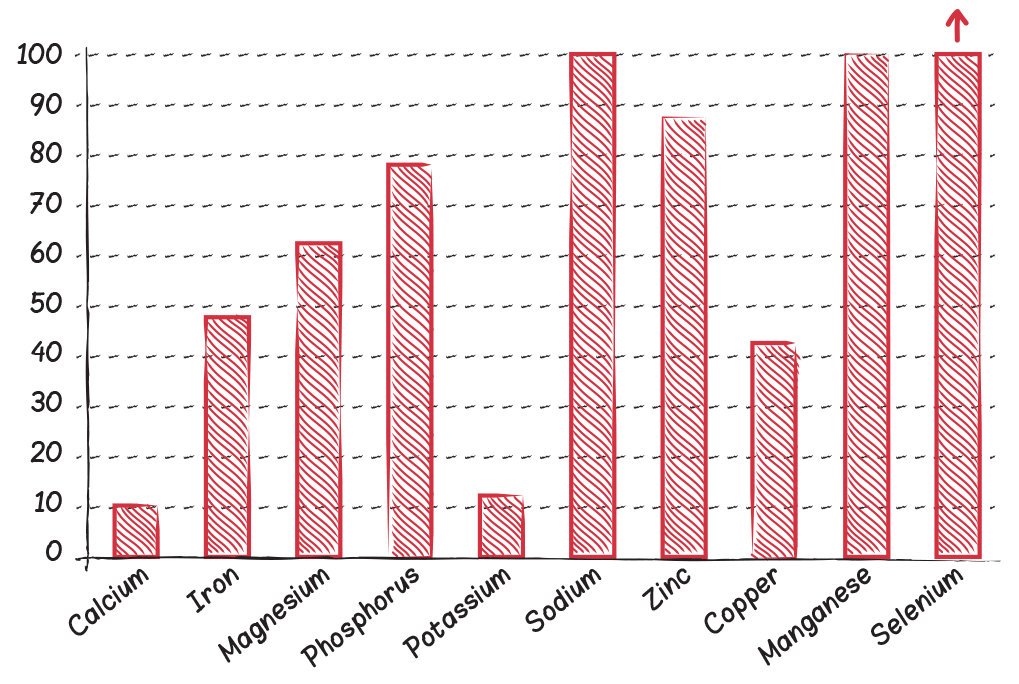

The graphs below show the relative content of vitamins and minerals in grains compared with vegetables, adjusted for caloric content, using eight of the most nutrient-dense whole-grain foods and fifty common vegetables. Values are expressed as the percentage of vitamin and mineral in grains compared with vegetables. For example, grains have about 10% of the vitamin E and calcium content that vegetables have. The only micronutrients for which grains can match vegetables are sodium and manganese. And the only micronutrient in which grains outperform veggies is selenium.

% vitamins in grains compared to veggies

% minerals in grains compared to veggies

Let’s emphasize that this is NOT making a case for avoiding grains completely—there are health benefits to moderate whole grain consumption. For example, a 2017 meta-analysis showed an 8% reduction in all-cause mortality (a general indicator of health and longevity) for each 30-gram (1-ounce) serving of whole grains daily, but no observed health benefit from refined grain consumption. Instead, this analysis shows the huge benefit of swapping out the excess grain servings we eat for more vegetables, while also choosing whole grains as often as possible.

In fact, when we look at the statistical relationships between vegetable consumption and mortality or disease risk, it becomes clear that the more vegetables we eat, the more protected we are. Every serving of fresh, whole vegetables or fruit we eat daily reduces the risk of all-cause mortality (a measurement of overall health and longevity) by 5% to 8%, with the greatest risk reduction seen when we consume eight or more servings per day. In fact, consuming 800 grams of vegetables and fruits daily reduces all-cause mortality by 31% compared to eating less than 40 grams daily. A 2017 meta-analysis showed that 2.24 million deaths from cardiovascular disease, 660,000 deaths from cancer, and 7.8 million deaths from all causes could be avoided globally each year if everyone consumed 800 grams of veggies and fruits every day! Wow!

Importance of Vegetables and Fruit

When we look at the statistical relationship between vegetable and fruit consumption and mortality or disease risk, it becomes clear that the more of them we eat, the more protected we are.

Yes, a major contributor to nutrient deficiencies and insufficiencies seen today is a holdover from previous dietary guidelines, too much emphasis on grains as a healthy food at the expense of vegetables and fruit, compounded with confusion over what constitutes a whole grain food, and a marked decrease in the fraction of Americans who are even paying attention to evolving USDA dietary guidelines, which are still rife with controversy and subject to criticism from nutrition experts.

The USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans own analysis highlights nutrient shortfalls even for those who follow the guidelines perfectly. The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (here) deliver insufficient amounts of potassium, magnesium (for men over 50), vitamin D, vitamin E, and choline; and the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (here) deliver insufficient amounts of iron, vitamin D, vitamin E, choline and vitamin B9 (folate). And of course, only about 9% of Americans are even trying to follow these dietary guidelines perfectly.

Nutrivore Is a Game-Changer—This FREE Guide Shows You Why

Sign up for the free Nutrivore Newsletter, your weekly, science-backed guide to improving health through nutrient-rich foods — without dieting harder —and get the Beginner’s Guide to Nutrivore delivered straight to your inbox!

Cause #3: Weight-Loss and Fad Diets

The good news is that you can increase the nutrient-density of your current diet by applying Nutrivore principles overtop of the core dietary structure.

Various diets billed for health and/or weight loss success have exacerbated the nutrient deficiency problem either through a lack of a nutrient focus and education or by omitting groups of nutritious whole foods, in some cases eliminating all food sources of certain nutrients. In fact, these diets focus on just about everything but nutrients, especially micronutrients but also nonessential (but super important) nutrients, representing a fundamental flaw in each dietary rationale. Instead, these popular diet plans teach an oversimplification of nutritional sciences or even a complete disregard for all scientific research that doesn’t conform to a diet’s preconceived notions. The result is that these popular diets purported to improve health or facilitate weight loss all fall short of the mark because nutritional deficiencies linked with increased chronic disease risk are still common among adopters.

Instead of explaining what to eat and why, most weight-loss and fad diets are defined based on what you eliminate, reduce, restrict or measure. What exactly you’re supposed to cut out will depend on which diet you’re following. You might be asked to reduce or eliminate completely: calories or carbs or fats or protein, gluten or dairy or soy, FODMAPs or sugar or starch or yeast, phytates or oxalates or lectins, plant foods or animal foods. You might also be asked to obsessively measure the quantities or relative ratios of allowed foods, which tends to increase our awareness of the foods we’re not eating, increasing the likelihood of disordered eating.

There are two main challenges that arise from defining diets this way.

First, the prevalent focus on weight instead of health propels yo-yo dieting and weight discrimination, using our body dissatisfaction to fuel the growth of the now $70 billion per year weight loss industry. An impressive collection of scientific studies prove that weight loss does not automatically make us healthier—indeed, thin and healthy are not the same thing; although they certainly can coexist, they don’t necessarily.

Studies have also shown that dichotomous approaches to diet, i.e., diets defined by a yes-list and no-list (or variations such as red-light versus green-light foods, or high-points versus zero-points foods), increase the risks both of developing eating disorders and regaining lost weight. Furthermore, the popularity of diets that demonize specific foods while lionizing others propels classism in diet and health—food elitism increases the cost of healthy foods. With Nutrivore, there are no “good foods” and “bad foods”, because we’re looking at the quality of the diet as a whole, fostering a healthier relationship with food.

It’s also worth emphasizing that there is a startling lack of scientific evidence supporting the claims of most of popular diets; and in fact, studies have failed to demonstrate superiority of any specific diet. Instead, studies demonstrate the benefits of eating patterns that: focus on whole and minimally-processed foods, emphasize plant foods, and avoid of overeating—eating patterns that are reinforced by the Nutrivore philosophy.

The second challenge with defining a diet based on food restrictions or eliminations is that, when we experience some success, however we measure it, by cutting out some foods, when we subsequently hit a wall, the intuitive next step for troubleshooting is cutting out more foods. As a result, we’re seeing the rise in popularity of ever more restrictive eating patterns, driving a problem that existed prior to our modern obsession with the beach bod: we tend to think of foods in terms of how it might harm us. Too many calories (or carbs or fat) might make us gain weight; sugar might give us diabetes or cause candida overgrowth; too much salt might raise our blood pressure; cholesterol or saturated fat might give us heart disease; protein is acidic; starch or FODMAPs or all plant foods feed the wrong kinds of bacteria in our guts; coffee, chocolate, and wine are vices that we should feel guilty about. Certainly, there is a scientific basis for some (and only some) of these associations; but this overly simplistic and cynical view of foods leads to avoidance of nutrients that, in moderation, are extremely beneficial. Biology is chock full of U-shaped response curves, where there’s a happy medium amount of something that supports health, yet too much or too little of that same thing is harmful. If we only think of something in terms of how too much is bad, we tend not to think about how enough is good. You may think the solution is “everything in moderation”, but unfortunately, this approach still fails to promote the most basic function of food: nourishment.

Applying Nutrivore to Your Preferred Diet

Of course, we all have complex reasons for following our preferred diet, it’s absolutely okay if you resonate with a specific dietary philosophy, choose a specific diet for religious or health reasons, or have found success with a specific diet and opt to continue following it because it works for you. Nutrivore is not a diet itself nor a substitute for your preferred diet, but instead a diet modifier that can be applied to your preferred diet to help you avoid common pitfalls from nutrient insufficiencies.

Nutrient Deficiencies in Popular Diets

Understanding the nutrient insufficiencies commonly associated with popular diets is essential for adopting the Nutrivore philosophy, with informed decision-making and by taking proactive measures to maintain optimal nutrition within your chosen eating plan. From vegan and vegetarian diets to low-carb, low-fat, gluten-free, paleo, primal, and ketogenic diets, each dietary approach presents unique challenges in meeting essential nutrient needs. By delving into the specifics of each diet and identifying potential deficiencies, you will gain a deeper understanding of the nutrients that require special attention.

The good news is that you can increase the nutrient-density of your current diet by applying Nutrivore principles and overlaying an emphasis on nutrient-sufficiency overtop of the core dietary structure, carefully selecting a wide variety of foods such that the body’s nutrient requirements are met by the diet.

If you follow a diet where all food sources of specific nutrients are eliminated, a Nutrivore approach can still be used to improve the quality of the diet. However, in these cases, its additionally important to work with a nutritionist, registered dietitian, or your doctor to identify nutrient shortfalls and supplement accordingly.

Learn What Foods Are the Best Sources of Every Nutrient

The Top 25 Foods for Every Nutrient

The Top 25 Foods for Every Nutrient e-book is a well-organized, easy-to-use, grocery store-friendly guide to help you choose foods that fit your needs of 43 important nutrients while creating a balanced nutrient-dense diet.

Get two “Top 25” food lists for each nutrient, plus you’ll find RDA charts for everyone, informative visuals, fun facts, serving sizes and the 58 foods that are Nutrient Super Stars!

Buy now for instant digital access.

Take-Home Message

The high prevalence of nutrient deficiencies and insufficiencies are the result of the complex confluence of the convenience of delicious and affordable ultra-processed foods with confusion over what foods are healthy and how much of them we should eat driven by both dietary guidelines and the messaging from the diet industry and weight-loss gurus.

Basically, it’s harder than ever to choose healthy foods and most people are confused about which foods those even are. That’s why Nutrivore is so important—we learn about what nutrients do in the body, how much of those nutrients we need, and which foods supply those nutrients. With this knowledge, it’s completely possible to choose foods to meet the body’s nutritional needs. Even better, there are many ways to do so, which means you can apply the Nutrivore philosophy to however you eat now.

Citations

Expand to see all scientific references for this article.

Bracci EL, Keogh JB, Milte R, Murphy KJ. A comparison of dietary quality and nutritional adequacy of popular energy-restricted diets against the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating and the Mediterranean Diet. Br J Nutr. 2021 Jun 21:1-14. doi: 10.1017/S0007114521002282.

Calton JB. Prevalence of micronutrient deficiency in popular diet plans. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2010 Jun 10;7:24. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-7-24.

Damms-Machado A, Weser G, Bischoff SC. Micronutrient deficiency in obese subjects undergoing low calorie diet. Nutr J. 2012 Jun 1;11:34. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-11-34.

Engel MG, Kern HJ, Brenna JT, Mitmesser SH. Micronutrient Gaps in Three Commercial Weight-Loss Diet Plans. Nutrients. 2018 Jan 20;10(1):108. doi: 10.3390/nu10010108.

English LK, Ard JD, Bailey RL, Bates M, Bazzano LA, Boushey CJ, Brown C, Butera G, Callahan EH, de Jesus J, Mattes RD, Mayer-Davis EJ, Novotny R, Obbagy JE, Rahavi EB, Sabate J, Snetselaar LG, Stoody EE, Van Horn LV, Venkatramanan S, Heymsfield SB. Evaluation of Dietary Patterns and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Aug 2;4(8):e2122277. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.22277.

Gardner CD, Kim S, Bersamin A, Dopler-Nelson M, Otten J, Oelrich B, Cherin R. Micronutrient quality of weight-loss diets that focus on macronutrients: results from the A TO Z study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Aug;92(2):304-12. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29468.

Gearhardt AN, Grilo CM, DiLeone RJ, Brownell KD, Potenza MN. Can food be addictive? Public health and policy implications. Addiction. 2011 Jul;106(7):1208-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03301.x.

Kant AK. Consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods by adult Americans: nutritional and health implications. The third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Oct;72(4):929-36. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.4.929.

Lee SH, Moore LV, Park S, Harris DM, Blanck HM. Adults Meeting Fruit and Vegetable Intake Recommendations — United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:1–9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7101a1

Light, L. (2006). What to Eat: The Ten Things You Really Need to Know to Eat Well and Be Healthy. United States: McGraw Hill LLC.

de Macedo IC, de Freitas JS, da Silva Torres IL. The Influence of Palatable Diets in Reward System Activation: A Mini Review. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2016;2016:7238679. doi: 10.1155/2016/7238679.

Marantz PR, Bird ED, Alderman MH. A call for higher standards of evidence for dietary guidelines. Am J Prev Med. 2008 Mar;34(3):234-40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.017. PMID: 18312812.

Nebl J, Schuchardt JP, Ströhle A, Wasserfurth P, Haufe S, Eigendorf J, Tegtbur U, Hahn A. Micronutrient Status of Recreational Runners with Vegetarian or Non-Vegetarian Dietary Patterns. Nutrients. 2019 May 22;11(5):1146. doi: 10.3390/nu11051146. PMID: 31121930; PMCID: PMC6566694.

Palascha A, van Kleef E, van Trijp HC. How does thinking in Black and White terms relate to eating behavior and weight regain? J Health Psychol. 2015 May;20(5):638-48. doi: 10.1177/1359105315573440. PMID: 25903250.

Schneeman BO, Ard JD, Boushey CJ, Bailey RL, Novotny R, Snetselaar LG, de Jesus JM, Stoody EE. Perspective: Impact of the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Report on the Process for the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Adv Nutr. 2021 Jul 30;12(4):1051-1057. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmab023.

Schüpbach R, Wegmüller R, Berguerand C, Bui M, Herter-Aeberli I. Micronutrient status and intake in omnivores, vegetarians and vegans in Switzerland. Eur J Nutr. 2017 Feb;56(1):283-293. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-1079-7. Epub 2015 Oct 26. PMID: 26502280.

Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G, Lampousi AM, Knüppel S, Iqbal K, Bechthold A, Schlesinger S, Boeing H. Food groups and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017 Jun;105(6):1462-1473. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.153148.

Teicholz N. The scientific report guiding the US dietary guidelines: is it scientific? BMJ. 2015 Sep 23;351:h4962. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4962. Erratum in: BMJ. 2015;351:h5686.

U.S. Trends in Food Availability and a Dietary Assessment of Loss-Adjusted Food Availability, 1970-2014, by Jeanine Bentley, ERS, January 2017

Food Availability (Per Capita) Data System, by Linda Kantor and Andrzej Blazejczyk , USDA, Economic Research Service, September 2022